Burning Scrolls

There are many names for the concept of the ‘World Brain’ I’m referring to within this thesis: A World Encyclopaedia, a Mundaneum, a universal library, a Docuverse, a universal knowledge hub, a Total Library, a Universal Bibliography [...]. But they all entail a similar thought, compiling the world’s knowledge in a universal/global system to influence social evolution, be it for scientific progression, education or peace. They vary in scope and implementation, but it’s the idea that counts for me, so at times the term can be used interchangeably depending on context.

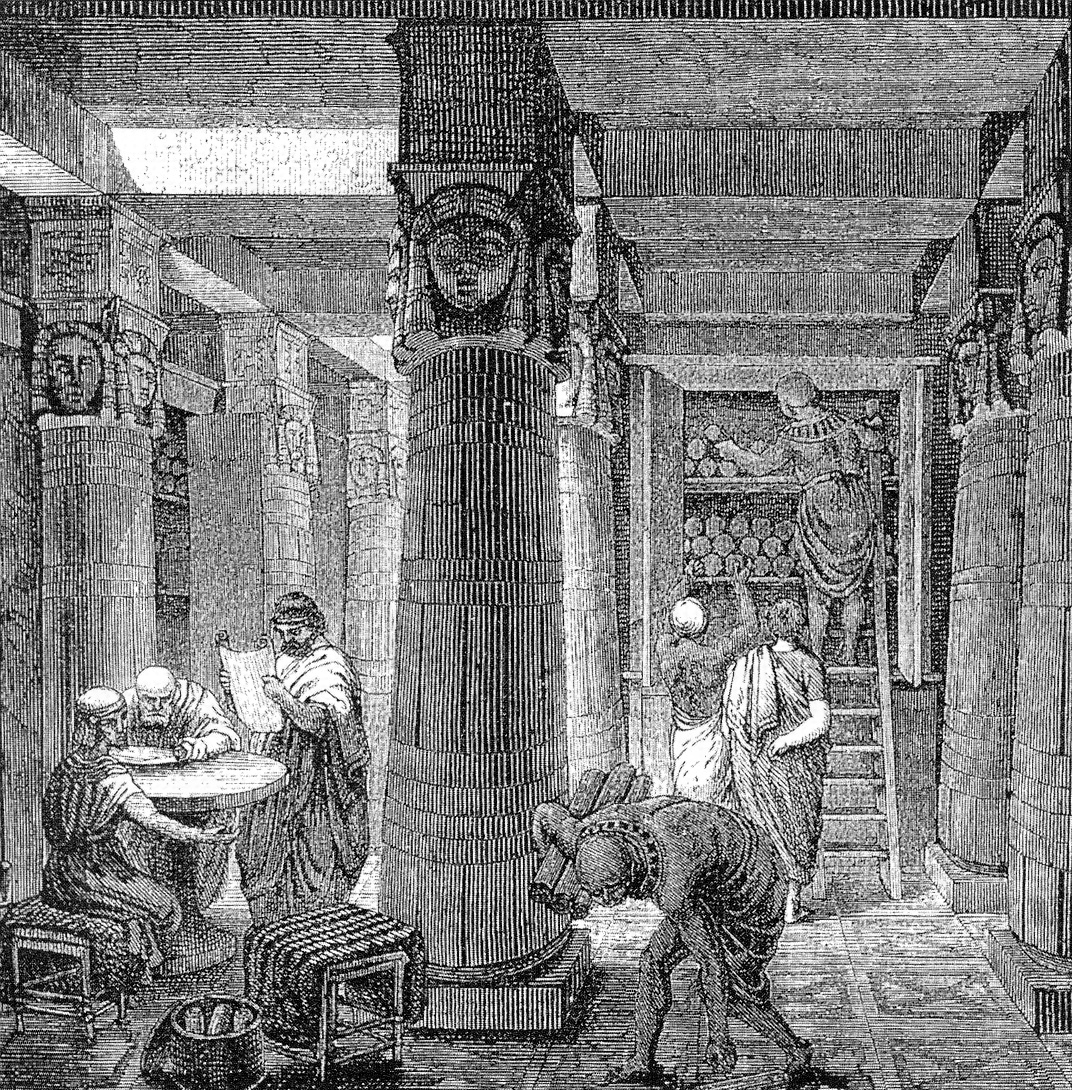

The first instance that comes to mind when thinking of a universal knowledge hub is the Library of Alexandria, as one of the most comprehensive and significant institutions of the ancient world, hosting an estimated 400,000 scrolls, which were catalogued in the Pinakes. It is often referred to as a famous example of a devastating loss of knowledge, due to a fire set by Caesar. But it seems like most of the library actually survived the fire and afterwards declined slowly. Either way, it serves as a reminder that we need to look after our collections of knowledge and be weary of centralisation. Now let’s follow that idea and fast forward 2000 years.

La Cité Mondiale

At the beginning of the last century in 1885, Paul Otlet and Henri Lafontaine (who later won the Nobel Peace Prize), two Belgian lawyers, were obsessed with the idea of creating a centre of the world’s knowledge. Globalisation was the hot topic and with a set of megalomaniac ideas stacked onto each other they ultimately planned to build some kind of world city of knowledge, the “Cité Mondiale”, for which Le Corbusier had already made some sketches. (Wright, 2014)

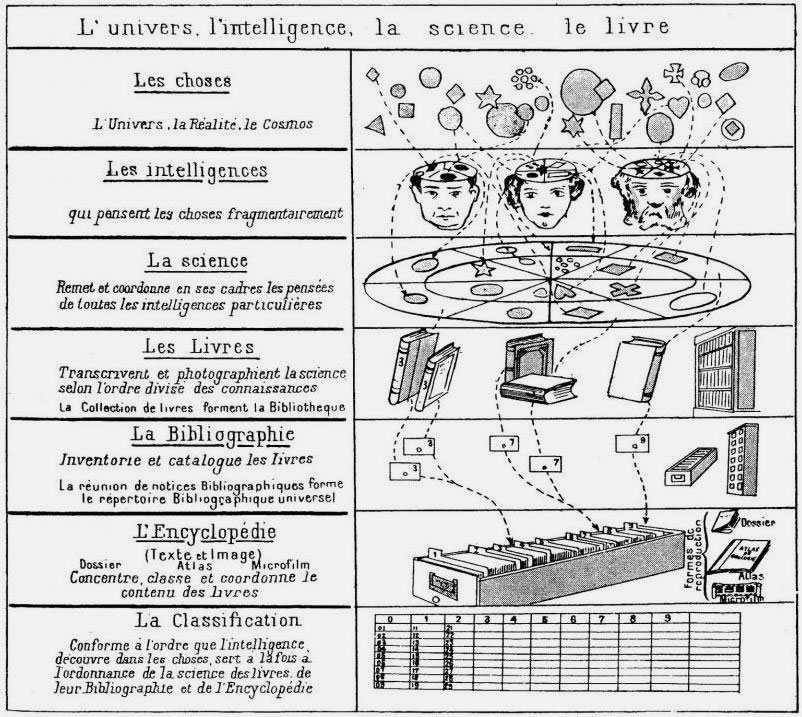

The heart of the project was the ‘Universal Bibliography’ a catalogue of all the world’s published information, recorded with the Universal Decimal Classification system, a top-down taxonomy created by Otlet himself, on 15 million index cards. They offered a fee-based service where people could mail in questions which would be answered by (mostly female) staff with copies of the fitting index cards. An analogue search engine if you will, that answered 1,500 queries a year by 1912. (Wright, 2014)

Mankind is at a turning point in its history. The mass of data acquired is astounding. We need new instruments to simplify it, to condense it, or intelligence will never be able to overcome the difficulties imposed upon it or achieve the progress that it foresees and to which it aspires.

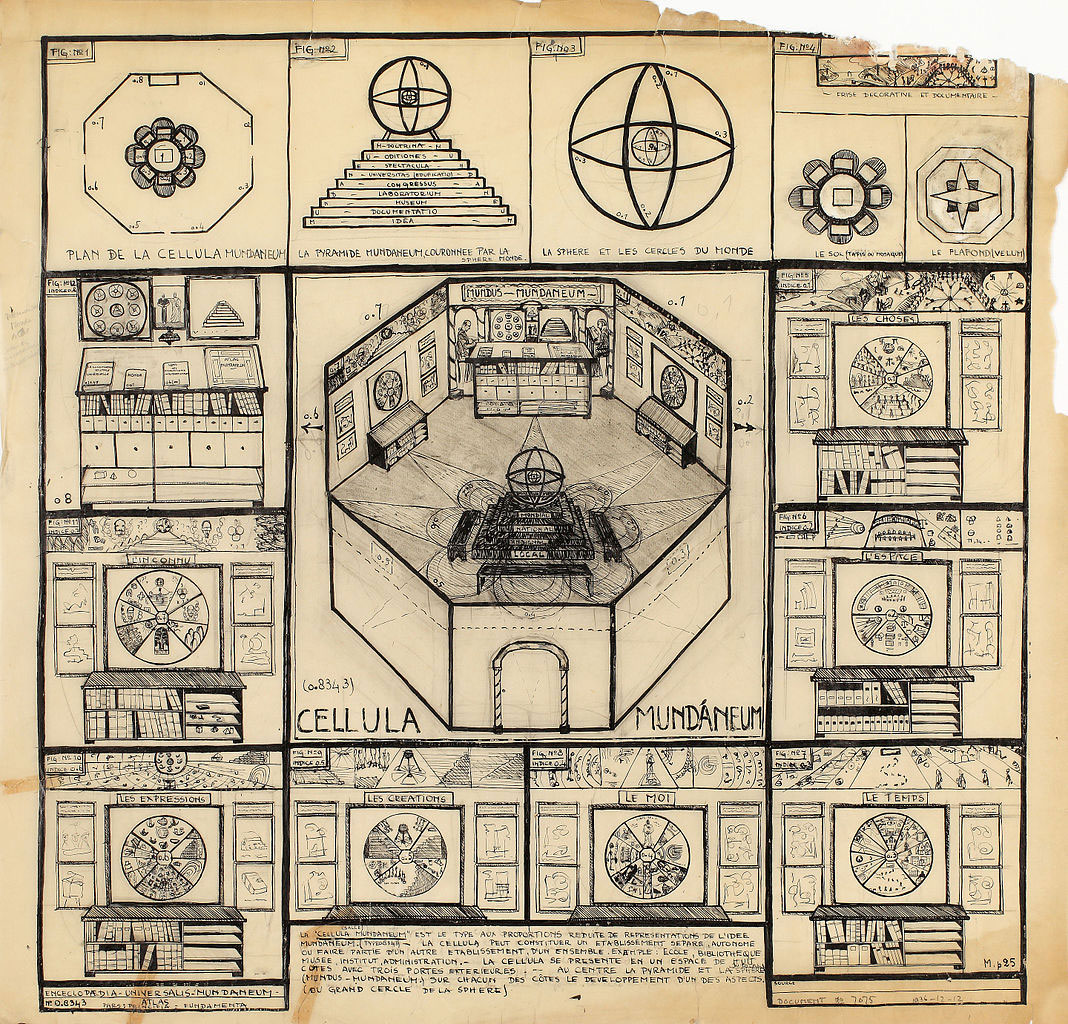

Around the 1930s Otlet extended his visions around the ‘Universal Bibliography’ by planning a world museum, the “Mundaneum” to not just refer to, but house the knowledge, accompanied by a world university and library, all within the city of knowledge. In his plans, this city would be host to leading institutions from all over the world and lead to peace. He was a convinced pacifist and later contributed to the development of the League of Nations and UNESCO.

Tragically none of his grand plans could be realised as Belgium was invaded by Nazi Germany in 1940, the Mundaneum got filled with third Reich art and his life’s work fell into obscurity. Just now he is starting to be recognized as some kind of forefather of information science.

Otlet envisioned the Mundaneum as a tightly controlled environment, with a group of expert “bibliologists” working to catalog every piece of data by applying the exacting rules of the Universal Decimal Classification.

Encyclopaedic Peace

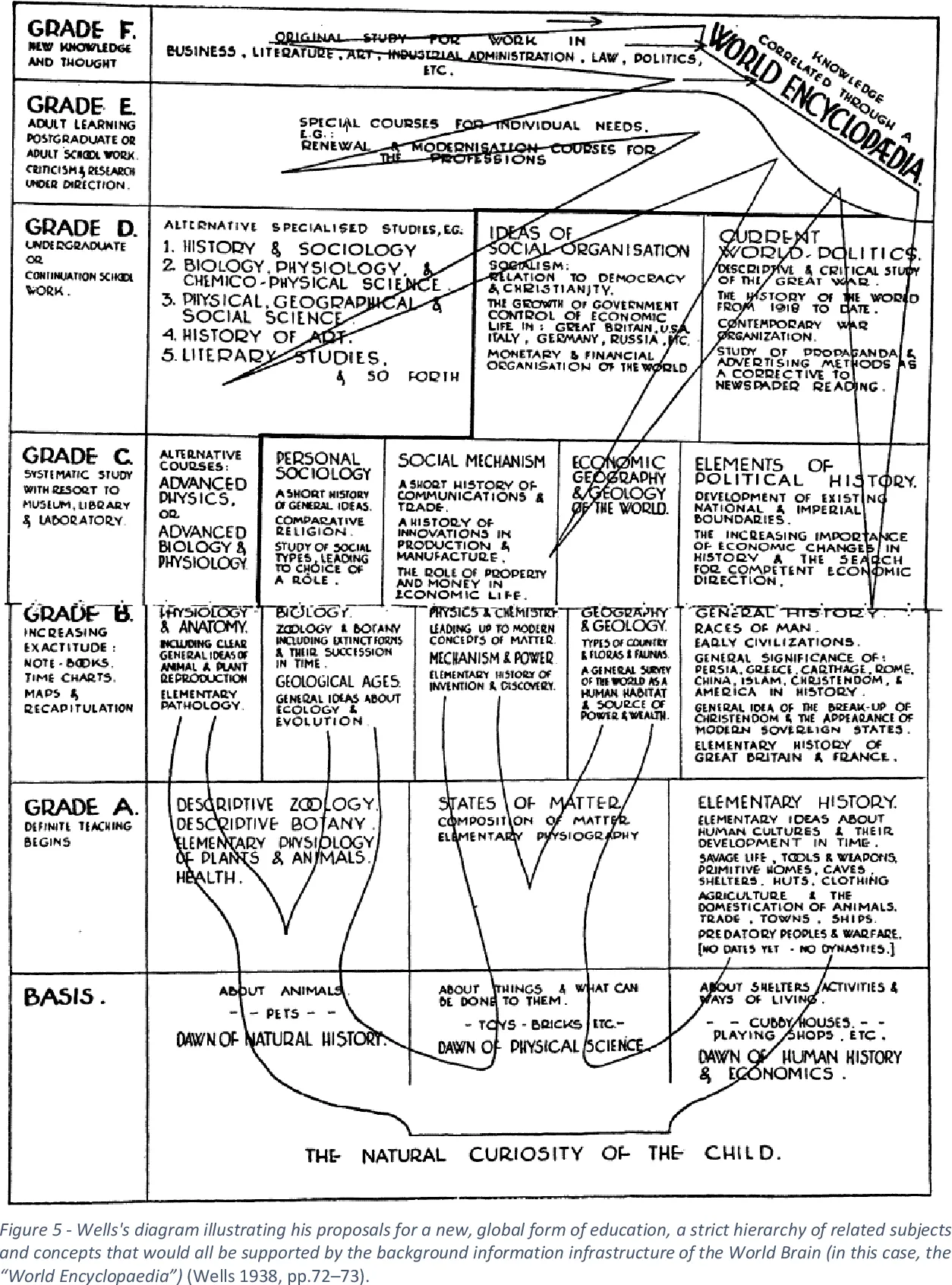

H.G. Wells, Outlet’s and La Fontaine’s contemporary and author of ‘The War of the Worlds’ as well as ‘The Time Machine’, was occupied with similar thoughts. In 1937 he published his essay ‘World Brain: The Idea of a Permanent World Encyclopaedia’. He too advocated for a global index of all bibliographies in the hope of it providing peace and development of human intelligence. The new technology of Microfilm to him was a possible solution to share the contents accordingly. (Wright, 2014)

These innovators, who may be dreamers today, but who hope to become very active organizers tomorrow, project a unified, if not a centralized, world organ to "pull the mind of the world together", which will be not so much a rival to the universities, as a supplementary and co-ordinating addition to their educational activities - on a planetary scale.

[...]

There is no practical obstacle whatever now to the creation of an efficient index to all human knowledge, ideas and achievements, to the creation, that is, of a complete planetary memory for all mankind. And not simply an index; the direct reproduction of the thing itself can be summoned to any properly prepared spot.

[...]

The whole human memory can be, and probably in a short time will be, made accessible to every individual.

[...]

Quietly and sanely this new encyclopaedia will, not so much overcome these archaic discords, as deprive them, steadily but imperceptibly, of their present reality. A common ideology based on this Permanent World Encyclopaedia is a possible means, to some it seems the only means, of dissolving human conflict into unity.

To me, it’s astounding how even in a completely analogue, tedious world it was taken for granted that the issue of information glut had to be tackled, come what may. What came, with all force, was a second World War, that set the world brain idea on ice for some years.