On Knowledge Transfer

To reproduce, an octopus mother will find a little underwater den, lay tens of thousands of eggs, carefully guard them and constantly move the water surrounding the little eggs, so fresh oxygenated water will flow between them. She doesn’t leave her place to hunt for months and would starve to death caring for the eggs before they even hatch.

Once the tiny octopus babies are out of their soft egg case, they are left all to their own devices and rely only on the instinct that is embedded in their DNA. There is no adult to teach them how to hunt for food, change colour to assimilate and squirt ink if they are in danger.

I once read that this lack of intergenerational exchange is why their species isn’t already taking over the planet. Their cognitive abilities are beyond impressive and work totally differently from the ones of mammals. Just imagine what an octopus society would look like if they wouldn’t take up most of their life learning everything from scratch, but built upon their parents’ knowledge, easily identify predators and learned about their ancestors.

Humans are different from all other known beings in that they acquire information, store it, process it and transmit it to future generations.

Just like Octomom, humans spend a lot of time and energy on their offspring. Somewhere in evolution we favoured the big brain and paid for it with a long pregnancy period. Luckily homo sapien mothers tend to survive birth and a period of intensive care for our youngest follows. Despite being so intelligent, or to become so, we take quite some time to reach the full capacity of our body and brain. During that period we learn from exploration, but those experiences are backed and extended by the knowledge of the adult generation, which builds upon their predecessors’. This, as Vilém Flusser puts it, “cultural memory” is what I’m interested in, our “unnatural” urge to remember.

Our species transmits acquired and inherited information from generation to generation. This doubly contradicts nature. The Second Principle of Thermodynamics states that information contained within nature tends to be forgotten. Living organisms contradict that principle by preserving and transmitting genetic information. They constitute a memory in defiance of the entropy of nature. Mendel's biological law states that acquired information cannot be transmitted from organism to organism. Our species contradicts that law by having an elaborate cultural memory, progressively storing acquired information to which successive generations have access. This double negation of nature, although only temporary, constitutes the human condition.

Throughout most of human history oral culture was the only way of preserving knowledge for future generations. Stories, songs and poems were the carriers of information and were stored through memory.

For many non-western cultures, oral tradition is still a core technology for transferring traditions and values.

Reading about oral culture made me think about my own upbringing, as I grew up with the palatinian dialect of southwest Germany. I learned to speak in a language (or at least a variation) that isn’t normed or noted down in a dictionary, where words and habituations can change from village to village and tonality is only readable through interpersonal interaction. I even remember learning a song, that I still know by heart, that describes what it means to be a palatinian.

Learn More

Material Culture

As early humans progressed and started using tools “material culture” was born. Materially stored Information has the advantage of externalising memory. The bits aren’t at risk of simply being forgotten anymore and aren’t subjected to the “errors of noise-disrupted transmission”

Hard objects have the advantage of being relatively stable. A stone knife can preserve information about 'how to cut' for tens of thousands of years. Information stored within hard objects creates informed objects that constitute our 'material culture'.

Flusser presumes that this material environment is what shaped our propensity to linearity. Translating oral storytelling, which works sequentially as an array of sounds, into objects embedded sequentiality in our culture.

this gesture can be recognized in the stringing of shells to make a necklace

From then on, throughout early human history this ‘common thread’ traverses until we reach a milestone: writing. With such a core technology unlocked, externalised knowledge could now be reconstructed by others independent from time and space, allowing a new level of abstraction and thought that helped humanity progress and keep a record of shared memory.

This development began with the lining up of stylized images (of pictograms) and ended with the aligning of phonetic signs (letters) into lines of text.

From then on there was no stopping, humans transferred their thoughts and knowledge to clay, wax, stone, papyrus, parchment, paper and the occasional wall. The start of a human record.

The Information Age

Now let’s fast forward roughly 5000 years. Paper, bound in books, has established itself as the medium of choice of the written word and Gutenberg invented the moveable-type printing press by 1440, kicking off the printing revolution. This enabled the grand public to extract written knowledge, as opposed to a selected few, which profoundly and permanently altered European society.

Let’s jump a bit further, by 1945 calculations of library expansion stated that every 16 Years our knowledge capacity would double if provided with enough physical space. To our luck, digital storage technology would be developed on time, or we would have drowned in paper at some point.

With the invention of the jacquard loom and its punched cards, humans had figured out a new binary system of storing information, that was clearer and more mathematical than language. A way to talk to machines and with that the start of analogue computing.

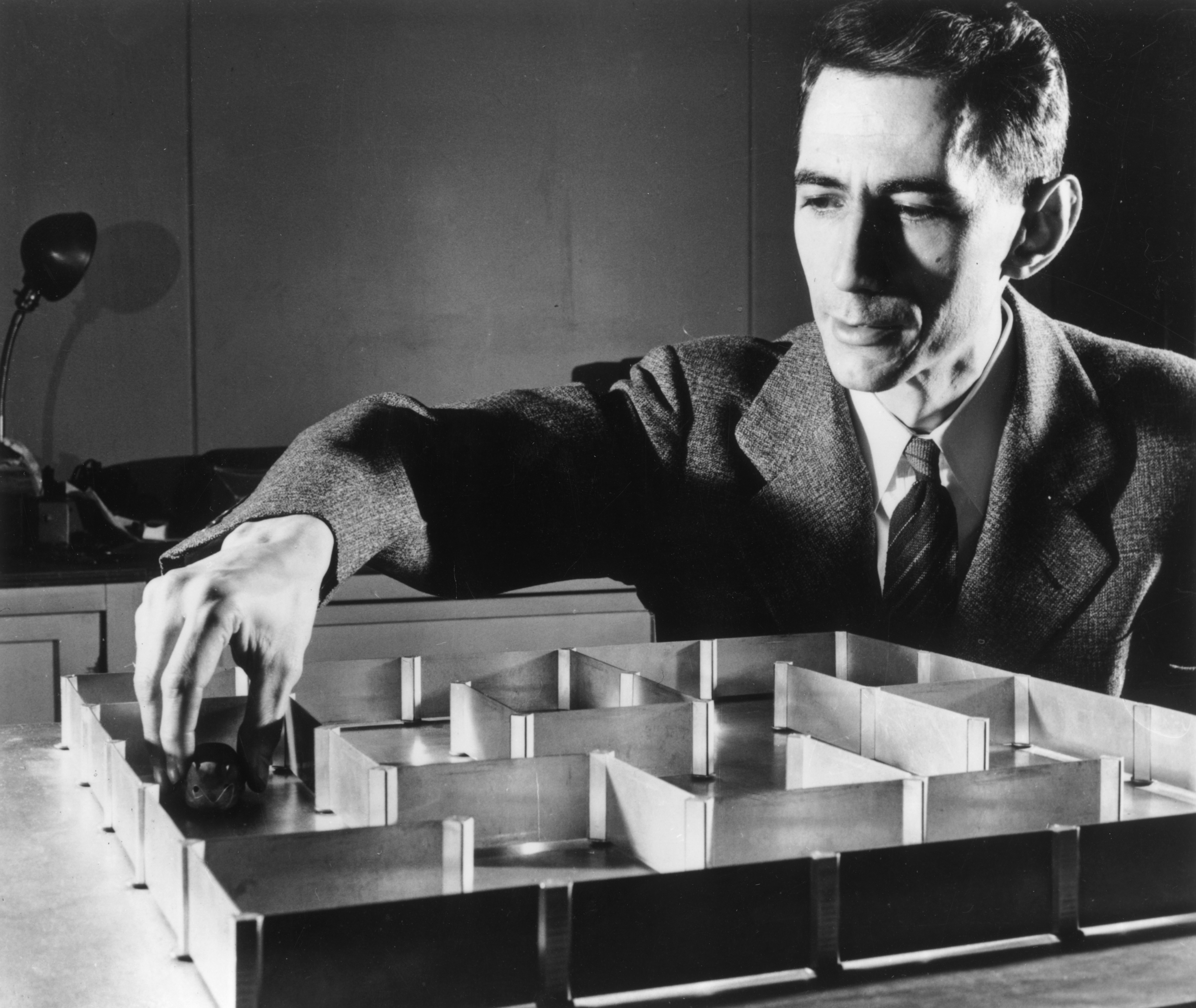

This logic, hole or not, yes or no, 1 or 0, is what inspired Claude Shannon, the forefather of information theory. In 1948 he defined it as a Bit, the smallest unit of information we know. With that digital information became quantifiable and programming and compression possible. Designers might recognize the term from Bitmaps, where a pixel is either rendered white or black.

These are exemplary pinpoints on the path towards the Digital Revolution, which marks the beginning of the Information Age. An enormous shift in society, sometimes compared to the Agricultural or Industrial Revolution, that’s still far from concluded. We’re living it right now.