The Web as Docuverse

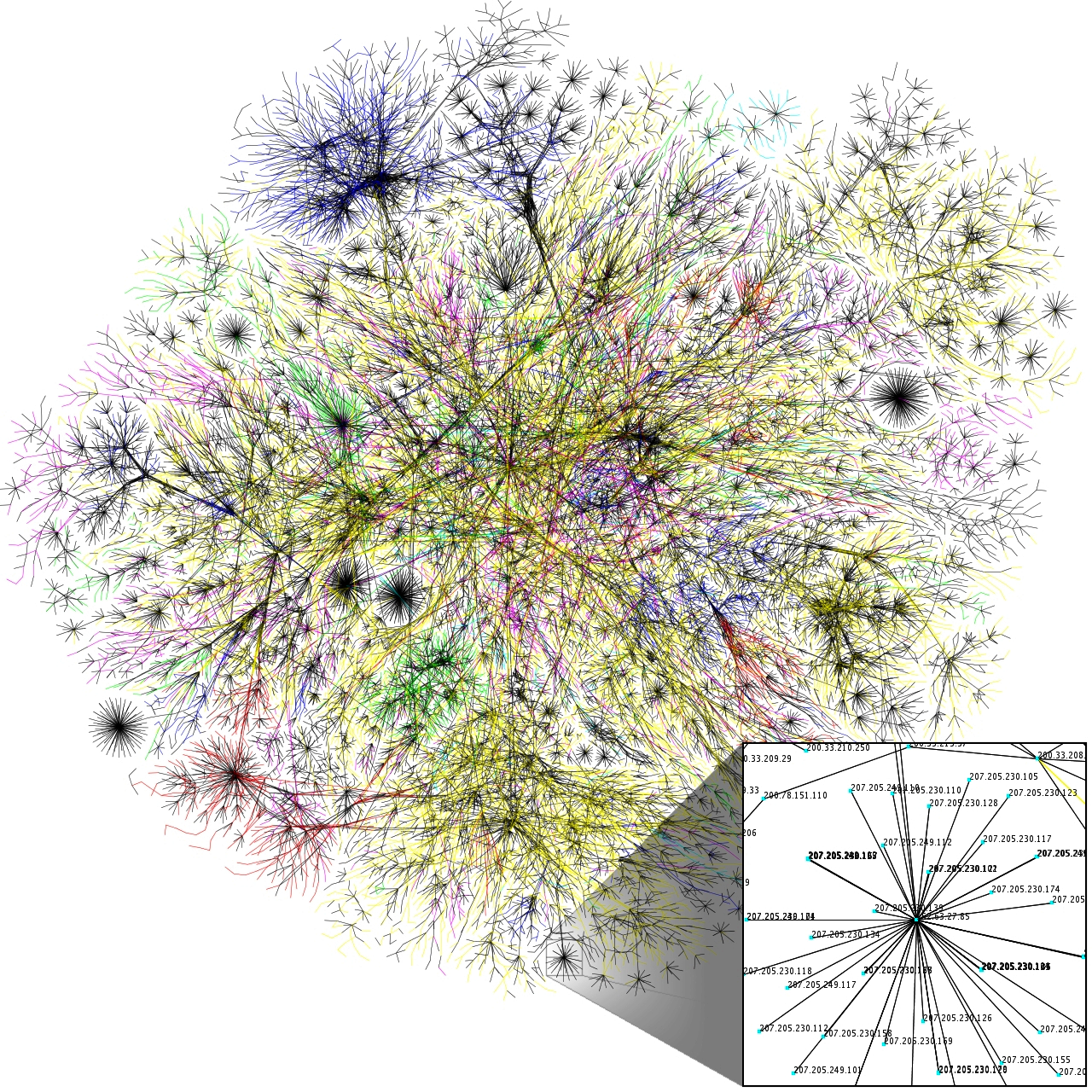

It’s hard to measure exactly, but according to Internet Live Stats, at the time of writing this thesis, there are 1.9 billion websites online (less than 200 million active) and 5,4 billion Internet users in the world. WorldWideWebSize puts it at a whopping 3,4 billion indexed pages, either way - it’s huge (Internet Live Stats - Internet Usage & Social Media Statistics, n.d.)(WorldWideWebSize.Com | The Size of the World Wide Web (The Internet), n.d.).

Without a doubt, the advent of the Web has been “central to the development of the Information Age” and catapulted itself to be the “world’s dominant software platform” (“World Wide Web” 2022) in a very short time span. It might be the most quickly adopted way of communication and sharing information in our species history.

Twenty years after Johannes Gutenberg invented his printing press, a bare handful of people in Germany and France had ever seen a printed book. Less than 20 years after its invention, the World Wide Web has touched billions.

Why exactly it took off the way it did goes beyond the scope of this thesis, but some of its advantages are for sure its compatibility with many devices, easy access to content as well as being fast, always up to date and easy to share. Certainly CERN’s decision to give it away through open access made a big impact and influenced much of the web 1.0 spirit of freely sharing data.

the Internet is one further step in the evolution of publishing, and the development of a universal online library of all the worlds’ knowledge is its inevitable and desirable outcome.

In the end, I think it’s great how the Web steamrolled its way into very established publishing and licensing systems and opened up some heads to the possibility of what accessibility could look like. A true grassroots equaliser that gave freedom of information to people that will be hard to take away again. It already reached so many that didn’t have a grasp before and with that greatly surpassed its hypertext predecessors, maybe because of its simplified many things at its beginning. An adapted royalties system must and will be found sometime.

The Xanadu hackers may never have produced a working implementation of their design, but they possessed a profound foreknowledge of the information crisis soon to be produced by digital technology. They were dead-accurate when they sketched a future of many-to-many communication, universal digital publishing, links between documents, and the capacity for infinite storage. When they started, they had been ahead of their time.

Andy Van Dam puts it quite well when asked about the Web’s ability as a host system to the world’s knowledge. To an extent, it is providing that experience, but most of the information is raw, of unknown origin and with that questionable reliability. He sees it as the human’s job now to make sense of it and actually build knowledge from surfing this sea of data and information. If you read Wikipedia you really have to go back to the primary sources. (Martin Wasserman, 2009)

The Web may not be the host to all of the world’s knowledge yet, but within its structure one of the closest resembling systems to the world encyclopaedia emerged: the wikis. And with that one wiki to rule them all, Wikipedia, the largest and most known encyclopaedia in the world. With 2 billion visits per month, it is the 7th most visited website, after search engines and social media. Even ranked before Pornhub, and probably is the only non-profit in the group.(Wikimedia Statistics - All Wikipedias, n.d.) (Meistbesuchte Websites - Top-Websites Ranking für September 2022, n.d.)

Wikis at their essence are a free and open hypertext system, they implemented the collaborative approach in building knowledge together, as a community at heart, accessible to everyone. They completely broke with the elite-based rule of thought by their ancestors, like the Encyclopaedia Britannica and can be seen as a stripped-down version of systems like FRESS or Intermedia. It makes it the best example we have today for a hypertext-based knowledge network striving to swallow all knowledge out there.

There is no central Wikipedia index, it is mostly navigated through search and linking, sometimes link lists, which makes it a low hierarchy system, with taggable pages. It even encourages that through its ‘random article’ button and a landing page filled with ever-changing wikilinks. Wikilinks are similar to hyperlinks, but each page features a ‘see also’ segment that fulfils a similar role as backlinks, which some wikis even implemented. It’s also possible to link to a non-existing page, to indicate it should be created.

The most complete realisation of the universal world encyclopaedia concept expounded by both Otlet and Wells is the Web-based encyclopaedia Wikipedia, which is universal in scope, far larger and complete than its predecessors, and freely licensed. However, although there are a myriad of rules and guidelines in place, it is operated entirely differently: by (usually anonymous) volunteers, and it exists as a registered charity, independent of any direct governmental or existing international association support and influence. In short, it is based on trust rather than expert authority, and can be considered a perfect demonstration of how the larger Internet as a whole differs from the predictions of Otlet and Wells.

Last Thoughts

Now, what do I make out of all this? Is the Web the hypertext system that entails our world brain? I don’t think so. Will it be? Time will tell. It definitely laid the groundwork, but 30 years aren’t long on the scale of human progression. We just got started with something exciting and carried our old conventions into that new realm, the next decades will show if the growing pains discussed above will be addressed and how. One thing I’m sure of though, the vision of colliding all of humanity’s knowledge into a universal system will further infect people’s minds. The Memex and Project Xanadu protruded between all these things I’ve read, they seem most influential because they represent an idea, a dream and haven’t met the compromise of reality. At the time the technology just wasn’t ready for their vision, but now it’s right there on the horizon.

To me the key technology to these universalist dreams is the Internet, I hope future generations will further relish this worldwide network. How we navigate it, how interfaces will change, all that is up to debate. Compared to the advent of the Gutenberg press, after which we established common norms, sizes and conventions, we’re in the middle of the said process of this ‘new’ medium.

Another thing that boggles my mind, is despite all efforts of shadow libraries and other entities like google, somehow the analogue book body of knowledge still hasn’t been appropriately swallowed and translated into the Web. Qualitative Wikipedia articles in the end just cite books in the good old way. Sure, uploaded PDFs make the ones online shareable, still they are somehow isolated, far away from an interconnected Xanadu network that will bring new knowledge to light through links. The reasons have been discussed before and I understand the complications, still we have to consider the implications of leaving this cultural heritage and treasure behind. I fear it will be much easier to just access digital information that the old knowledge might be neglected and we can’t let that happen.

For all its limitations, however, the Web’s colossal success serves as a ringing vindication of its forefathers’ vision. While it may be far from perfect, the Web has proved to be an enormously important democratizing technology. It is a profoundly humanist medium, open, accessible, and largely populated by nonprogrammers who have found ways to express themselves using a panoply of available technologies.

It’s interesting to me how the motivations that drove progress to Web technology, ideas of sharing knowledge and collective knowledge building, and scholarly ideology, don’t truly reflect the Web we have today. Maybe they were a bit delusional? To me, the present Web shows that most of what we do everyday isn’t academic at all.

What surprises me though is, that as soon as Web technology was there and growing exponentially it seemed to have swallowed a whole generation of hypertext scientists that believed in systems that could do so much more. Intermedia and Hypercard were so complex, well-engineered and functional, still somehow our desktop environments today don’t reflect that referentiality they pioneered. Why did those educational or personal knowledge bases just stop and leave us with plain word processors, the document metaphor and enclosed PDFs?

Now I know, all this is expected a little too much from the Web. I made sure to beat around on all its shortcomings in comparison to previous functionalities, but if we can learn one thing from Xanadu it’s that we shouldn’t expect everything from one single system. Ted tried to push all his hopes and dreams into it, how could it ever fulfil them?

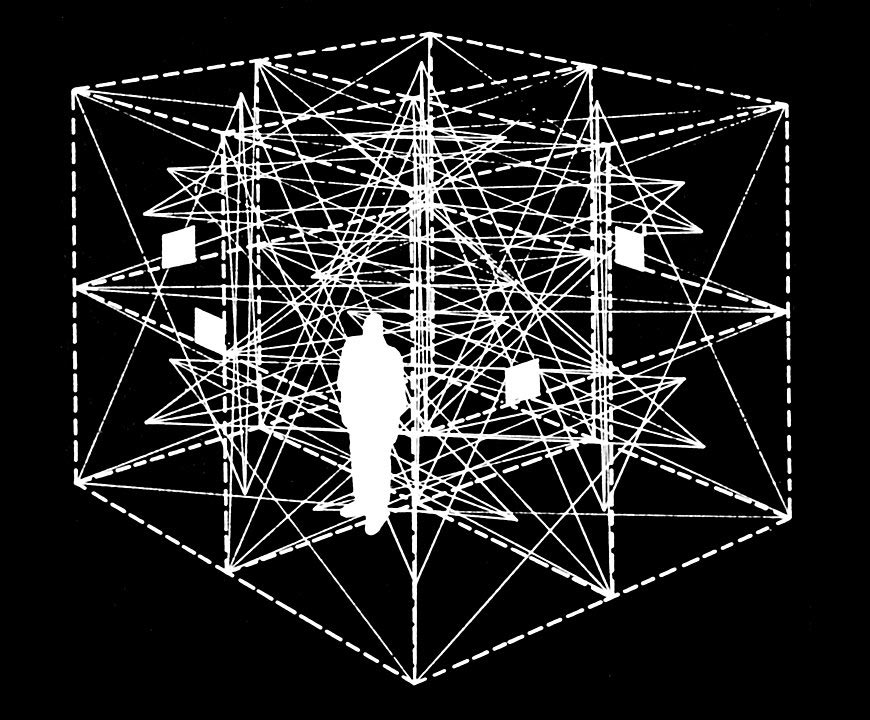

The Web has already proven to be so much more than we expected from it, why not build a new, improved, separate internet-based system for scholastic purposes? One that can live up to the complex demands of academic work, that would encourage scholastic discourse without drifting apart like a comment section. One with multifunctional links and shareable trails. One that grants transcluded, traceable references and that can be archived properly. A Xanadu that doesn’t try to swallow everything all at once and ends up being a nightmarish Library of Babel, and a Wikipedia comprising all important books, where scholars and students produce new knowledge alike, supported through a smart royalties setup. One can dream at least, right?

Such a system will represent at last the true structure of information (rather than Procrustean mappings of it), with all its intrinsic complexity and controversy, and provide a universal archival standard worthy of our heritage of freedom and pluralism.

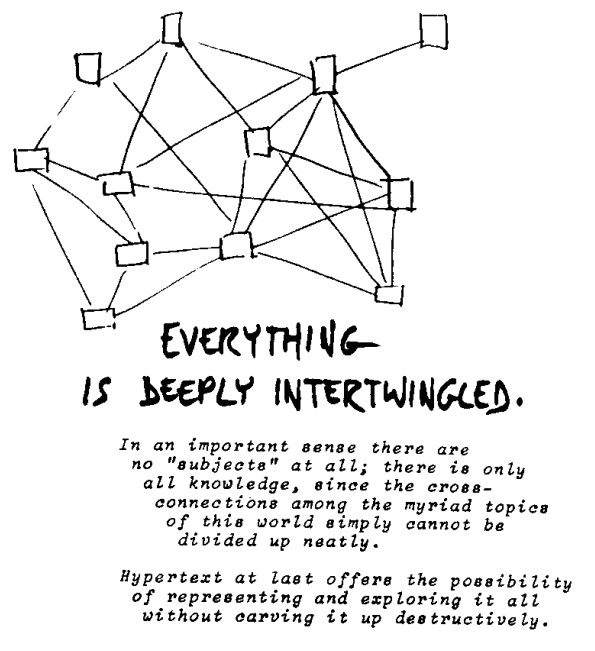

We are but knots within a universal network of information flux that receive, process and transmit information.