If we imagine all the books of the world in one big library, there are still some pitfalls that the classical codex format brings with it. One: Its physicality. Even apart from its high flammability, susceptibility to moisture and acidity, it can be a pain to handle.

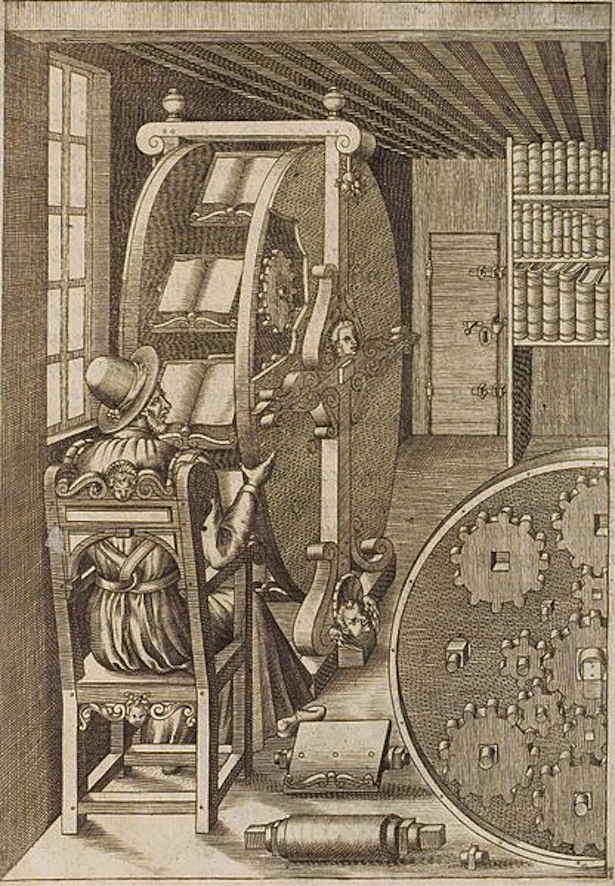

Working scholarly means knowing many texts and contrasts of opinions, information that spreads over multiple different volumes. And it takes quite some time and effort to make connections between different sources. So thought Augostino Ramelli, who must have been sick of dealing with the large and heavy printed works of his time. He invented a kind of ‘book ferris wheel’ to sit at and read multiple books in one location with ease, especially “for those who are indisposed and tormented by gout.”

In comparison to the earlier scrolls, the book format, through its browsable pages, made it easier to navigate a text. To extract knowledge from a scroll, it needed to be rolled meticulously section by section - the ultimate linear format. Still, the book as we know it is held together by a thread, holding the pages in a fixed sequence, sorted from the beginning to the end, from introduction to conclusion, from A to Z. Until today this linearity is deeply embedded in our literary tradition.

A fundamental challenge in writing is representing the non-linear world in a linear medium. We’re used to arguments and stories unfolding in a line. Rhetoric and narrative have developed strategies like the syllogism and the flashback for dealing with a multidimensional world in a single path. As successful as these strategies are, they remain constrained to a linear sequence. Traditionally, readers have had little choice but to follow along.

Breaking Linearity

But what if we imagine the document only as a container, holding a collection of chunks of information that can be extracted and used in other contexts? What if we only could pull up the information that is relevant to us at that time? And what if that information could even exist outside of its home document structure and be shared?

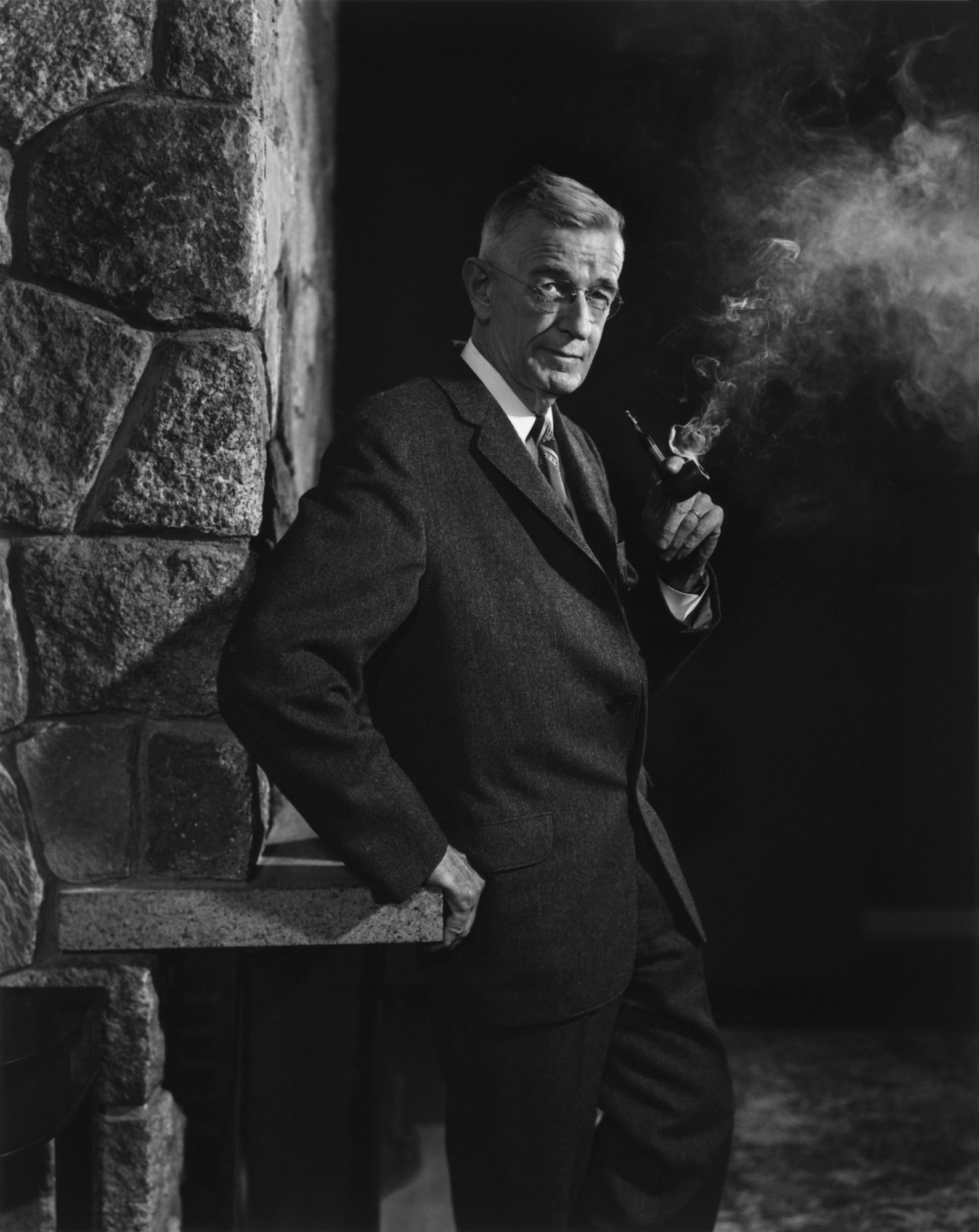

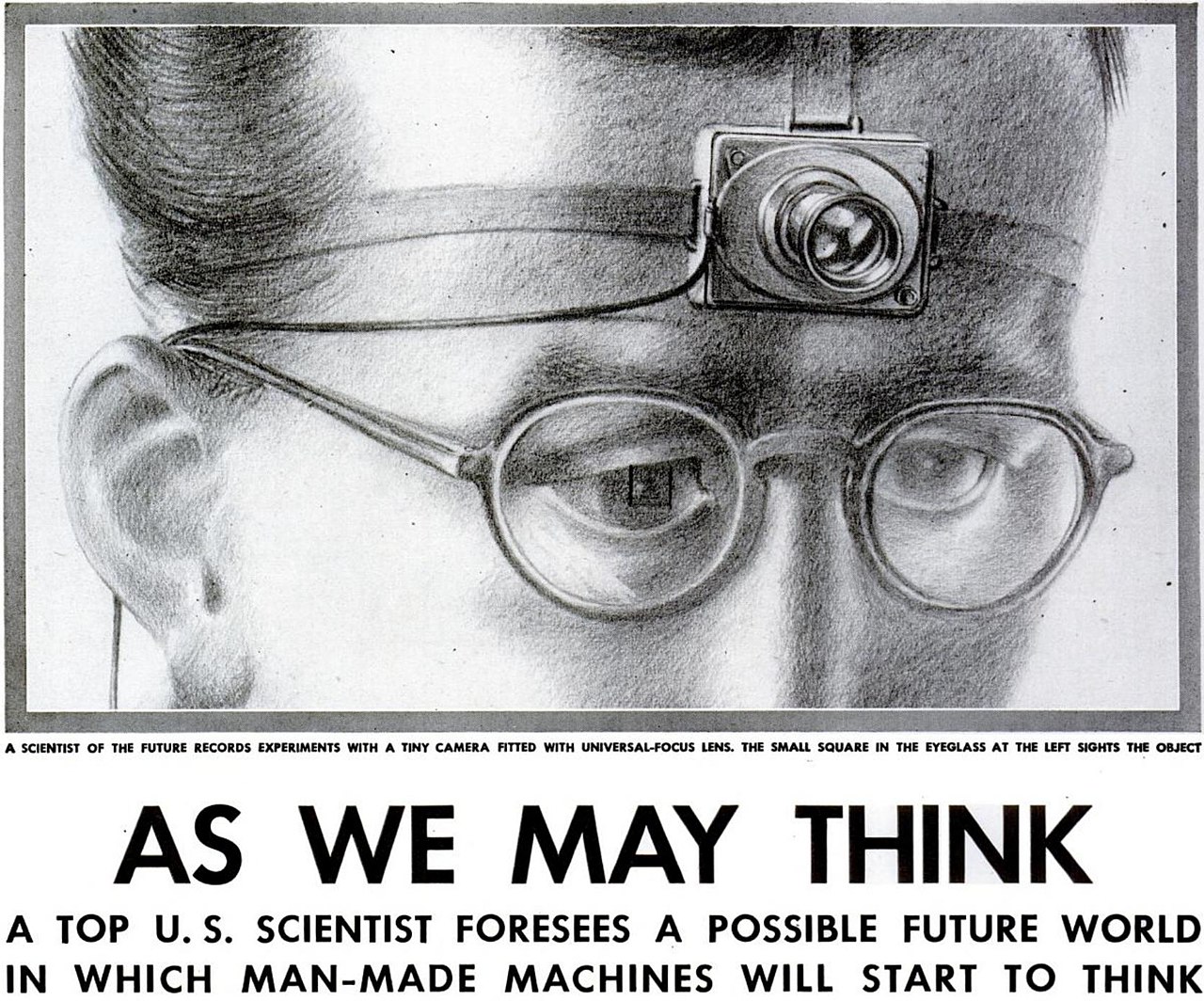

In 1945, right after the end of World War II, Vannevar Bush published an article contemplating these questions in The Atlantic called ‘As We May Think’, which would influence many to come and cause ripples which are still relevant today.

Bush wasn’t just anyone, he was a scientist who had become an important figure during the war, as President Roosevelt’s science advisor and by being involved in the Manhattan Project. He before had made relevant contributions to analogue computing with the differential analyzer at MIT and would later contribute to the creation of the National Science Foundation.

He was upset by the inefficiency of scientific progress due to information overload and eager to direct this progress towards better use than destruction, so he introduced a fictional machine that would aid people in navigating Information.

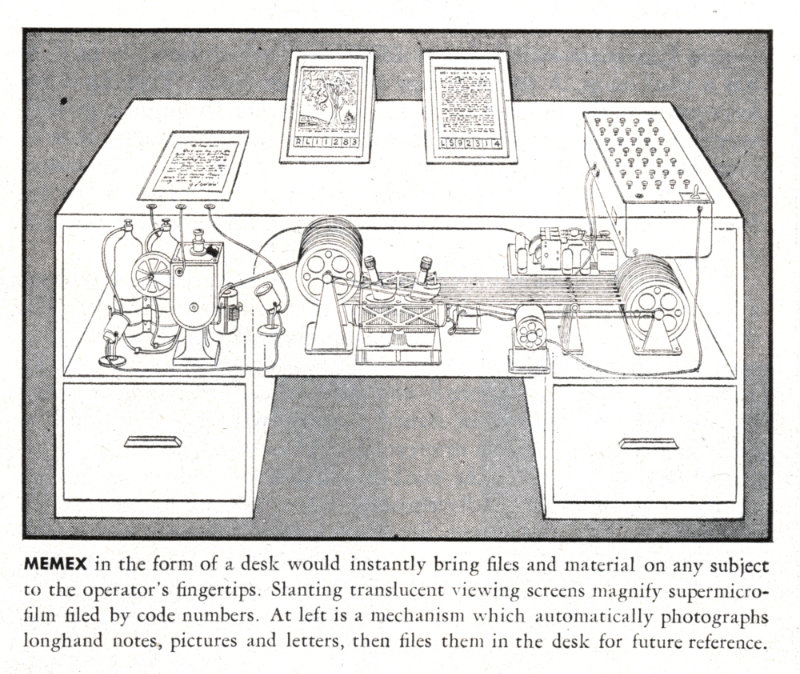

Consider a future device for individual use, which is a sort of mechanized private file and library. It needs a name, and, to coin one at random, "memex" will do. A memex is a device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory.

Bush suggests Microfilm, which could be pulled up mechanically, as the solution for storing a lot of information within his desk like Memex. He imagined the Encyclopaedia Britannica, reduced to the size of a matchbox.

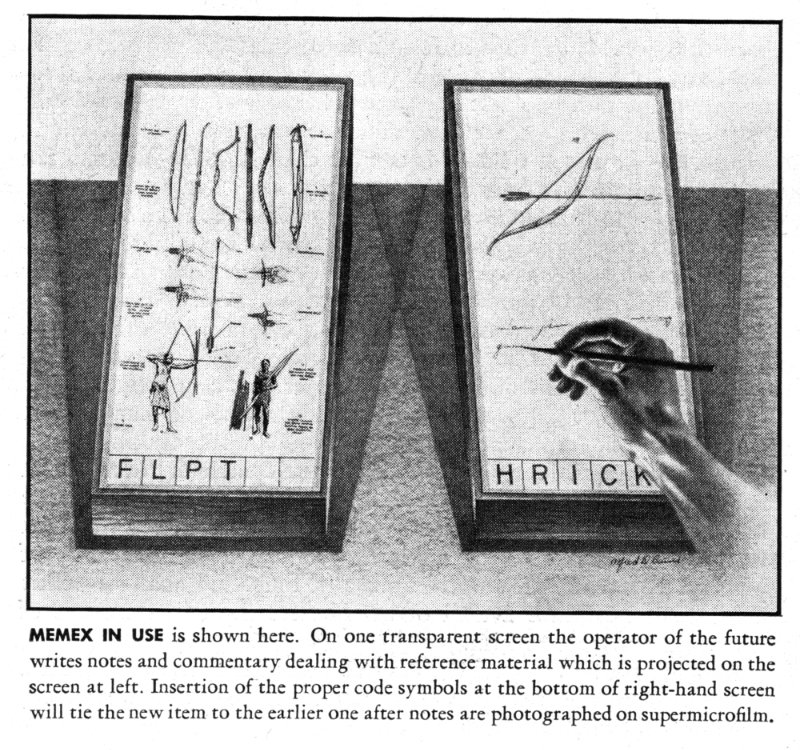

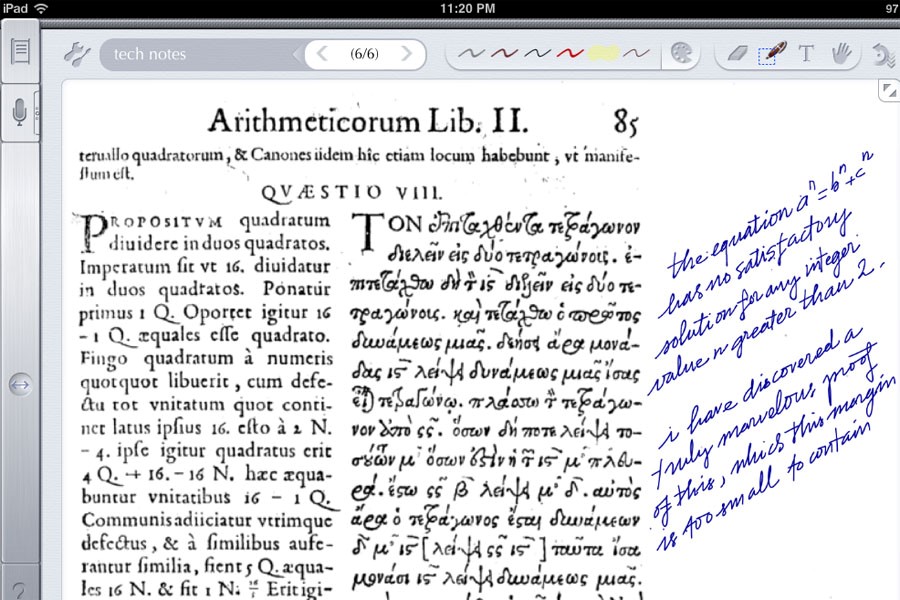

As he has several projection positions, he can leave one item in position while he calls up another. He can add marginal notes and comments

margins of Arithmetica, an example of how important

annotations can be.

Convinced that the human brain works differently than static top-down indexes, he proposes making paths or trails that would link pieces of information together to form new ideas, just like thoughts can jump from one point to the other.

associative indexing, the basic idea of which is a provision whereby any item may be caused at will to select immediately and automatically another. This is the essential feature of the memex. The process of tying two items together is the important thing.

It is exactly as though the physical items had been gathered together from widely separated sources and bound together to form a new book. It is more than this, for any item can be joined into numerous trails.

And just like that he had predicted what would later become ‘personal computers’ and delivered the probably first description of what we now call ‘hypertext’.

Presumably man’s spirit should be elevated if he can better review his shady past and analyze more completely and objectively his present problems. He has built a civilization so complex that he needs to mechanize his records more fully if he is to push his experiment to its logical conclusion and not merely become bogged down part way there by overtaxing his limited memory. His excursions may be more enjoyable if he can reacquire the privilege of forgetting the manifold things he does not need to have immediately at hand, with some assurance that he can find them again if they prove important.

The common intellectual heritage shared by each of Otlet, Wells and Bush is their persistent use of the analogy of the human brain in relation to the free and unrestricted flow of information within society, and how their predictions would result in an external information infrastructure which complemented the internal workings of the mind.

Learn More

Tying Connections

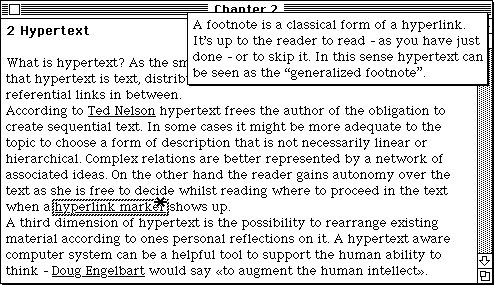

Two decades later Ted Nelson, who had been inspired by Bush’s Memex and who thought a lot about these connections, coined the term ‘hypertext’ in his conference paper ‘Complex information processing: a file structure for the complex, the changing and the indeterminate’.

Let me introduce the word "hypertext"***** to mean a body of written or pictorial material interconnected in such a complex way that it could not conveniently be presented or represented on paper. It may contain summaries, or maps of its contents and their interrelations; it may contain annotations, additions and footnotes from scholars who have examined it.[...]***** The sense of "hyper-" used here connotes extension and generality; cf. "hyperspace." The criterion for this prefix is the inability of these objects to be comprised sensibly into linear media, like the text string, or even media of somewhat higher complexity.

Later he specified it a little further, as non-linear text.

Well, by "hypertext" I mean nonsequential writing—text that branches and allows choices to the reader, best read at an interactive screen.

Hypertext surpasses ‘traditional’ text. It can do more than just contain its own information because it provides connections to other nodes. Those links allow readers to jump from an anchor to the reference and follow that path that might as well lead away from the ‘main’ text they started at, or jump them between paragraphs within said starting point. Through that, they can explore the context or relationships between the content.

Since hyper- generally means "above, beyond", hypertext is something that’s gone beyond the limitations of ordinary text. Thus, unlike the text in a book, hypertext permits you, by clicking with a mouse, to immediately access text in one of millions of different electronic sources.

What sets it apart is its networked structure and with that the dissolving of the linearity of text. It is easy to imagine those as divisions within the text but a text itself being built of multiple text chunks.

When interacting with Hypertext readers become active, they select their own path through the provided information just like in “Choose Your Own Adventure” books, but with possibly far more complex outcomes and trails.

Nelson even took the idea a step further by incorporating connected audio, video, and other media in addition to text. He named this extension of Hypertext "Hypermedia." In order to keep this thesis within a defined framework, I solely focus on hypertext. While some of the systems discussed are in line with the definition of hypermedia, this concept includes much more that would go beyond the scope.

literature appears not as a collection of independent works, but as an ongoing system of interconnecting documents.

Ted Nelson argues that most of literary culture has already worked as a hypertext system, through referentiality. Page numbers, indexes, footnotes, annotations and bibliographies are the original analogue paper equivalent to links.

Many people consider [hypertext] to be new and drastic and threatening. However, I would like to take the position that hypertext is fundamentally traditional and in the mainstream of literature. Customary writing chooses one expository sequence from among the possible myriad; hypertext allows many, all available to the reader. In fact, however, we constantly depart from sequence, citing things ahead and behind in the text. Phrases like “as we have already said” and “as we will see” are really implicit pointers to contents elsewhere in the sequence.

Traditional print works by “inclusion.” External references are embedded as quotations, becoming integral parts of the referring text.

With this definition a book could be seen as a sequence of citations and commentaries on commentaries, the Talmud is an example of that. It emphasises that literary practice is contextual and referential in its nature as is culture itself.

These thoughts could be continued with concepts of intertextuality and post-structuralism. Hypertext literature or hypertext fiction are further areas to be investigated, but all surpass the scope of this thesis.

Dreams of the Docuverse

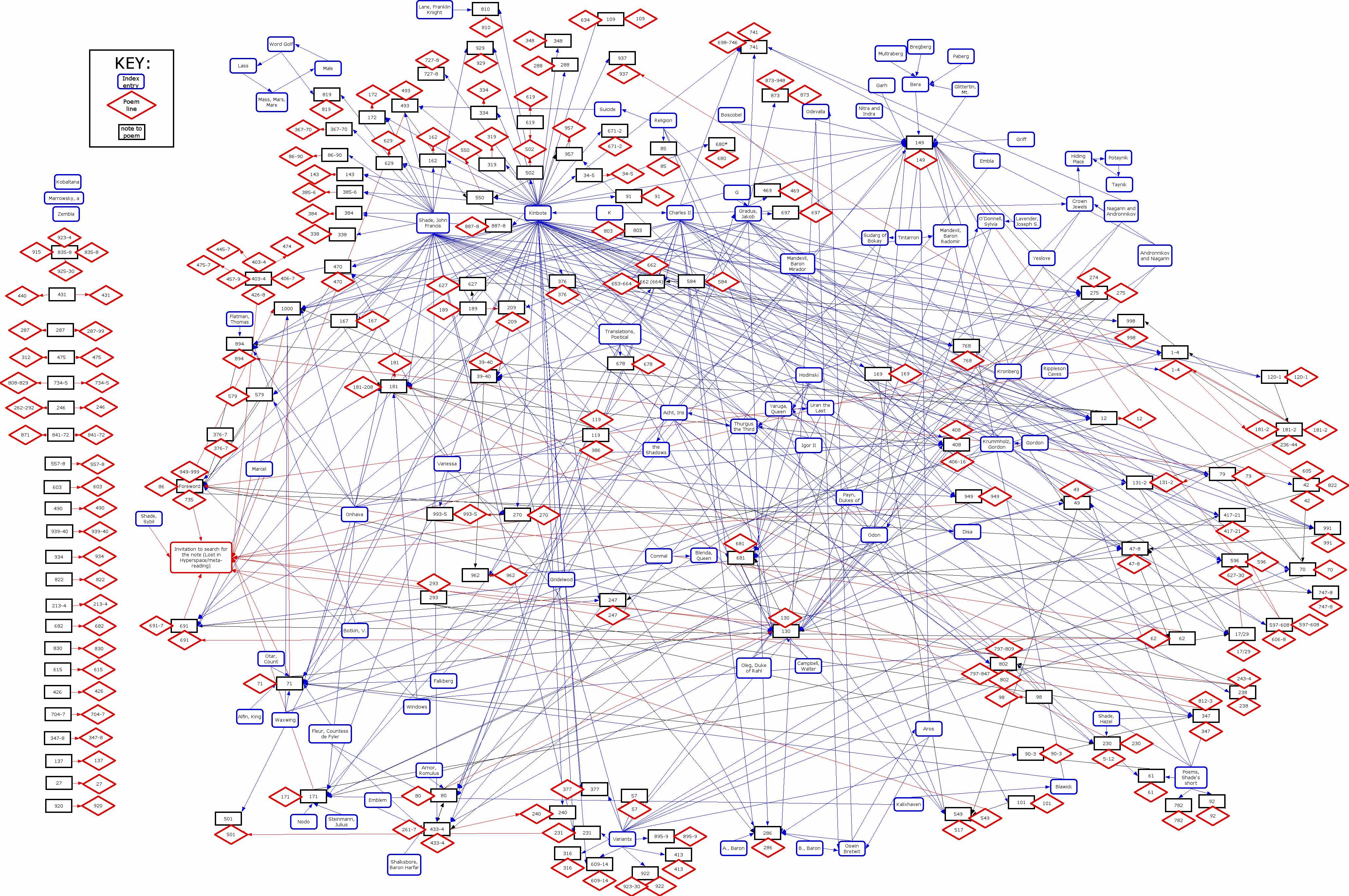

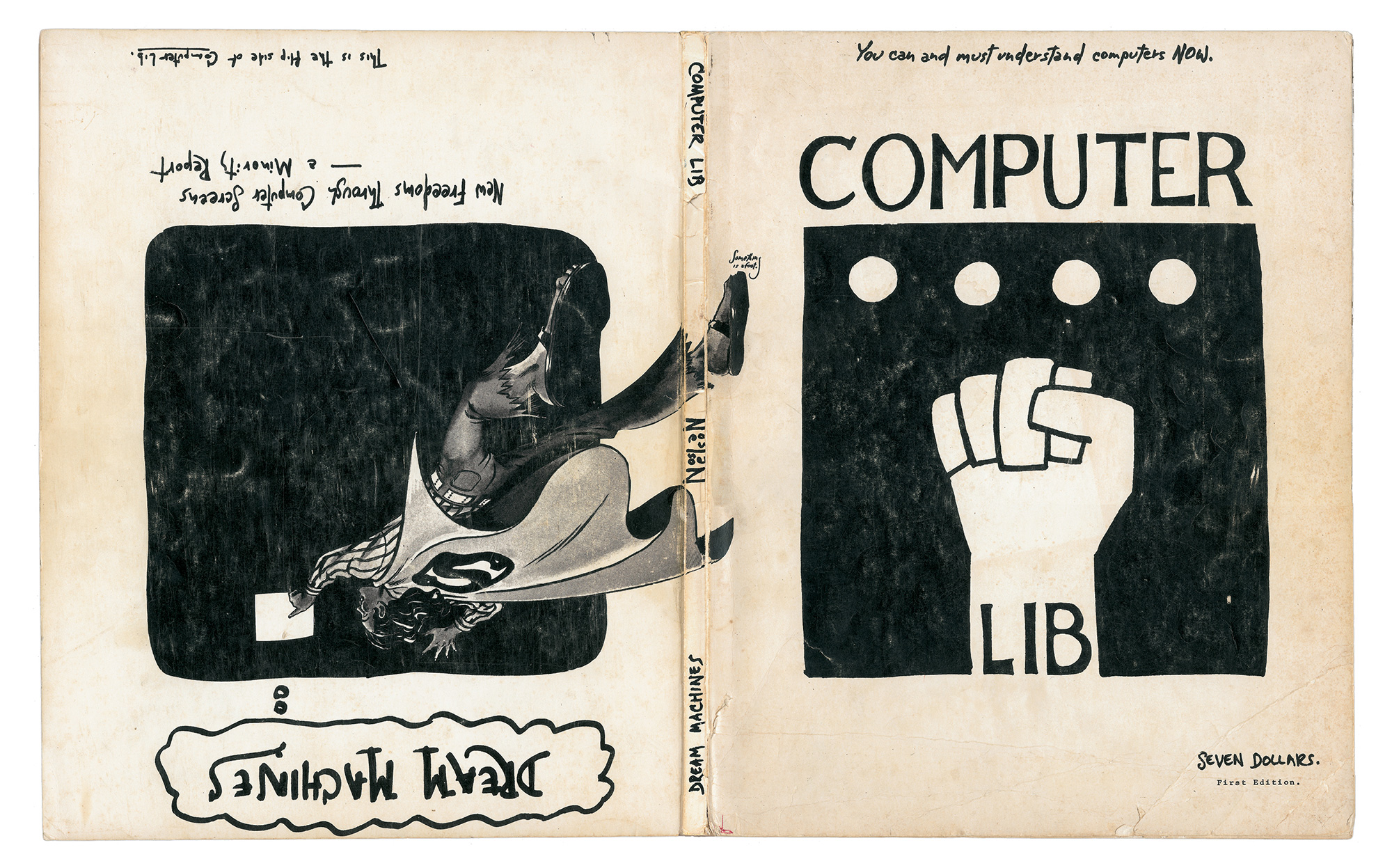

Project Xanadu is the brainchild of Ted Nelson who, when he coined the term hypertext in the 60s only saw it as a part of the bigger system named after the poem "Kubla Khan" by Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Xanadu partly is a yet unrealized utopia, partly an incomplete working prototype, partly living on in other projects. It’s hard to compile a good overview of what Xanadu entails in a compressed form like this, but I will try.

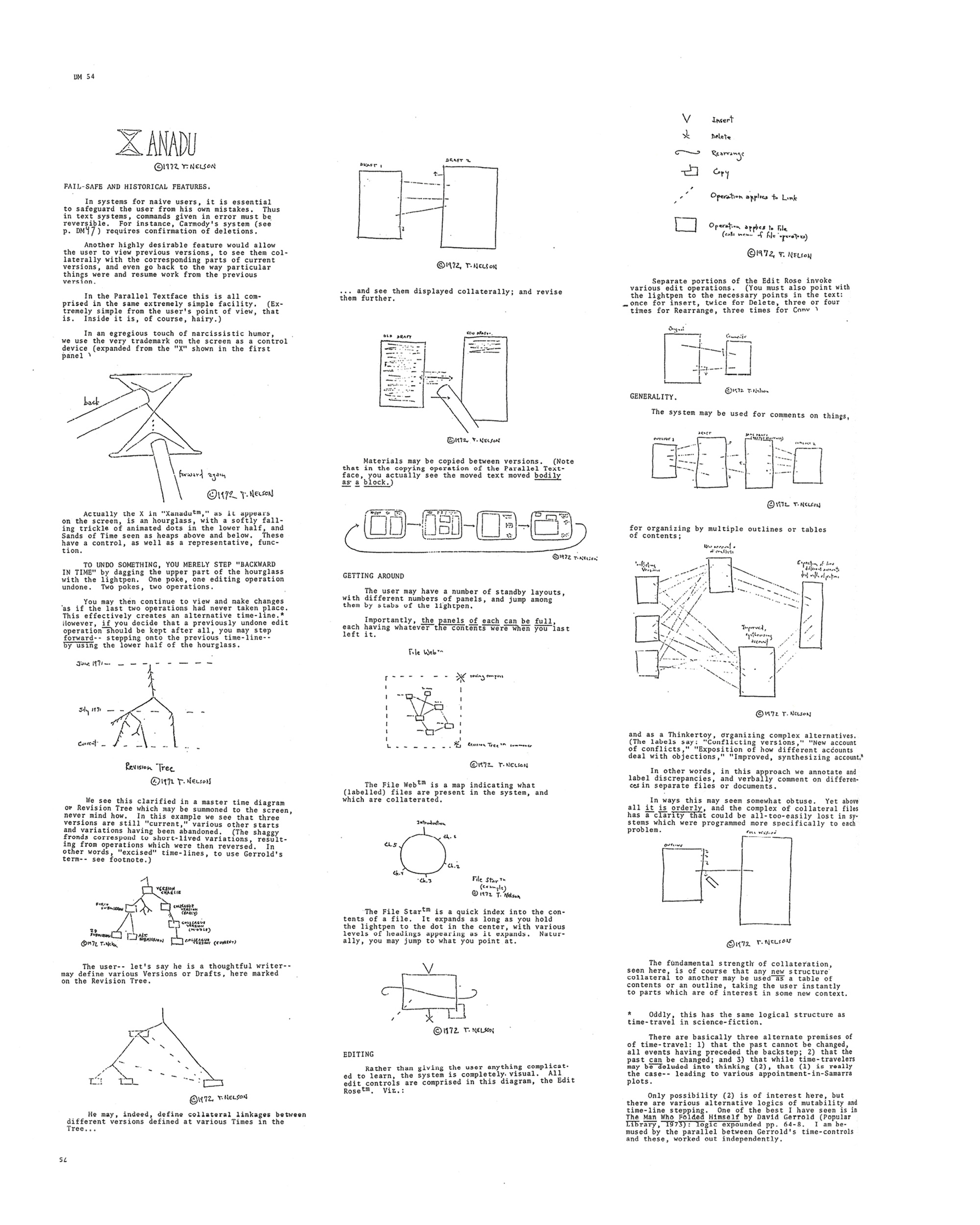

Ted had coined the word hypertext in 1963 to mean “non-sequential writing”, and in 1966, had proposed a system called Xanadu in which he wanted to include features such as linking, conditional branching, windows, indexing, undo, versioning, and comparison of related texts on an interactive graphics screen.

Nelson started thinking about the ways we could deal with text on computers and electronic publishing during his graduate sociology studies at Harvard when he took a computer science course. Radically open to new ideas, but quite understanding of the problems at the time, Ted, a generalist/philosopher rather than a programmer, started to add up his ideal visions of a universal repository hypertext network.

Following Bush’s footsteps he imagined all existing documents in one big network, the “Docuverse”. He was the first to see a connection in how digital computers could facilitate the idea of a “world brain” in the future. How we could store, present and work with information.

Now that we have all these wonderful devices, it should be the goal of society to put them in the service of truth and learning.

In the docuverse there is literally no hierarchy and no hors-texte. The entire paratextual apparatus inhabits a horizontal, shared space.

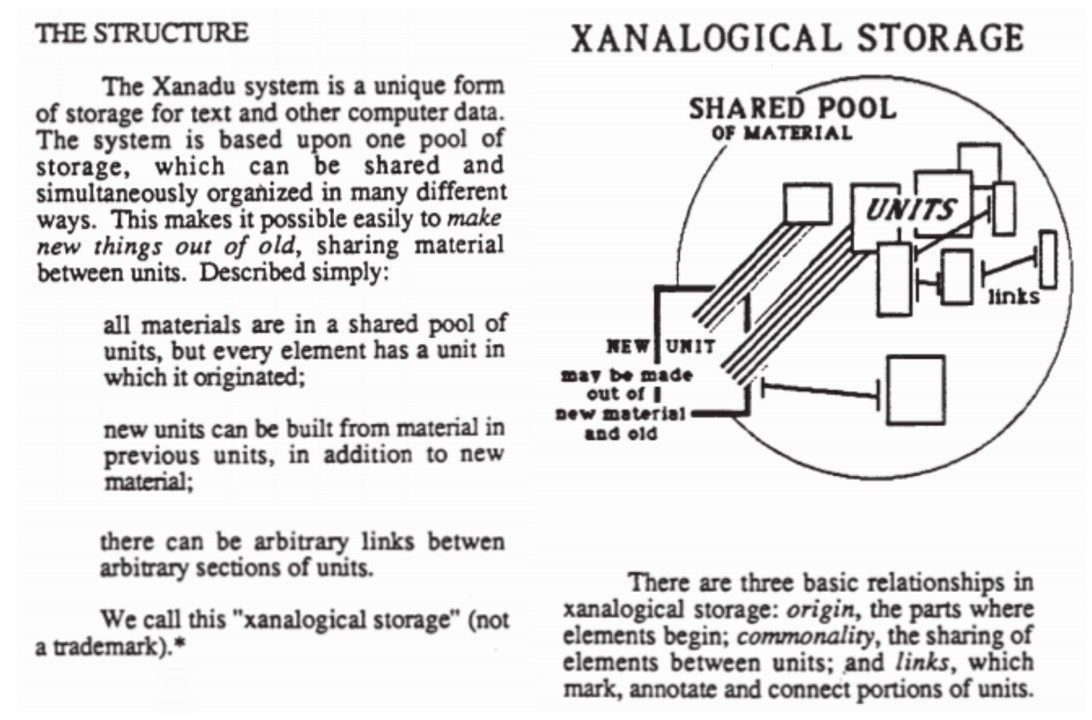

He was (and still is) convinced that all these connections and relationships between documents could now finally be represented in a digital dataset, just like a digital version of Otlet’s Mundaneum, but not just referring to content but actually hosting the knowledge itself including all of its metadata and previous versions.

The point of Xanadu is to make intertextual messiness maximally functional, and in that way to encourage the proliferation and elaboration of ideas.

Within this net of interwoven connections, all references and quotes could be traced back to their original text and even earlier versions of those in one big network. A new commodity that would advance humanity just like Bush and Wells had imagined.

Now we need to get everybody together again. We want to go back to the roots of our civilization-- the ability, which we once had, for everybody who could read to be able to read everything. We must once again become a community of common access to a shared heritage.

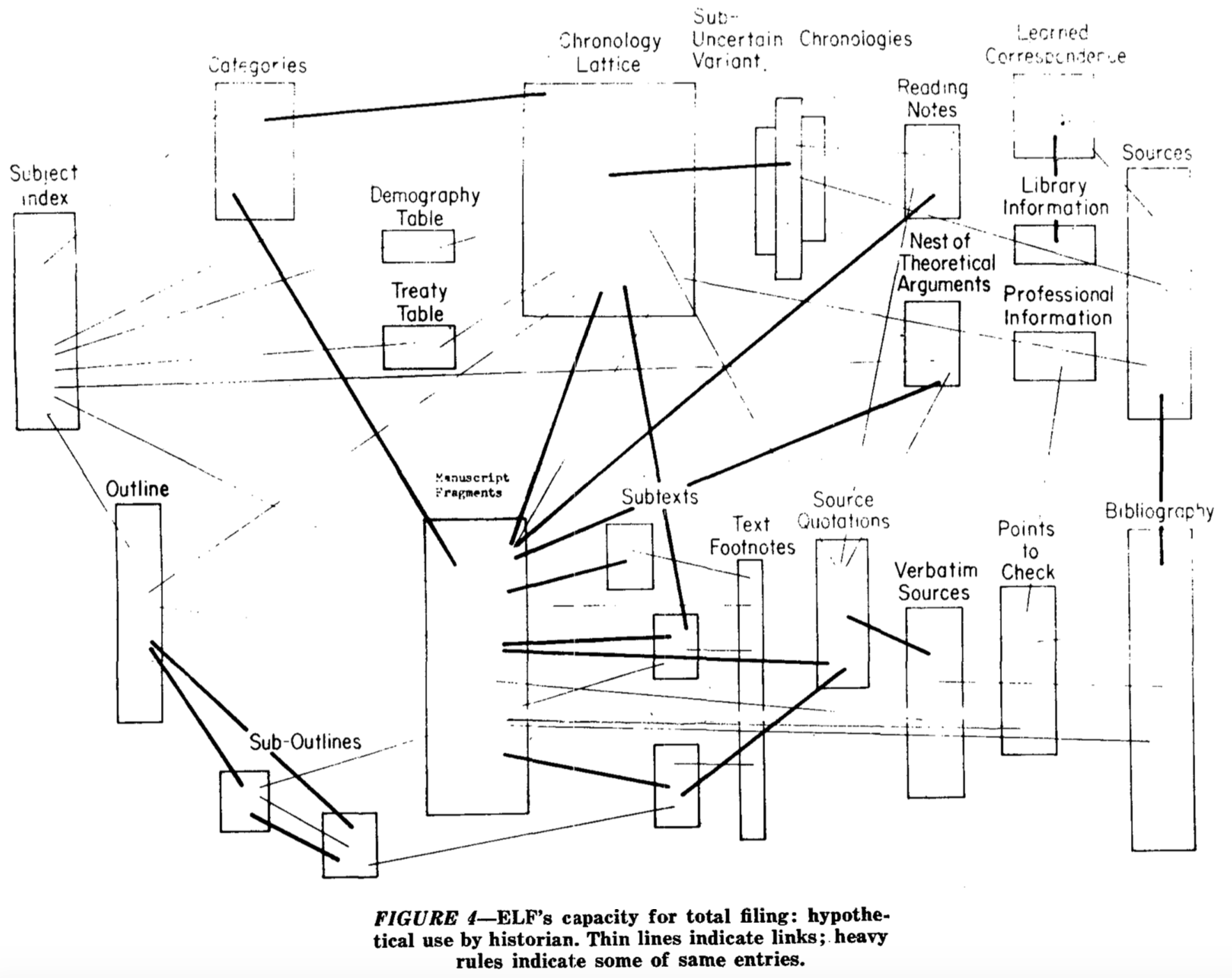

His vision encompassed bidirectional links that went into both directions and were granular about which exact part they reference. He defined different types of hypertext, depending on the level of referentiality.

Basic or chunk style hypertext offers choices, either as footnote-markers (like asterisks) or labels at the end of a chunk. Whatever you point at then comes to the screen.

Collateral hypertext means compound annotations or parallel text.

Stretchtext changes continuously. This requires very unusual techniques, but exemplifies how "continuous" hypertext might work.

An anthological hypertext, however, would consist of materials brought together from all over, like an anthological book.

A grand hypertext, then, folks, would be a hypertext consisting of "everything" written about a subject, or vaguely relevant to it, tied together by editors

The real dream is for "everything" to tie in the hypertext.

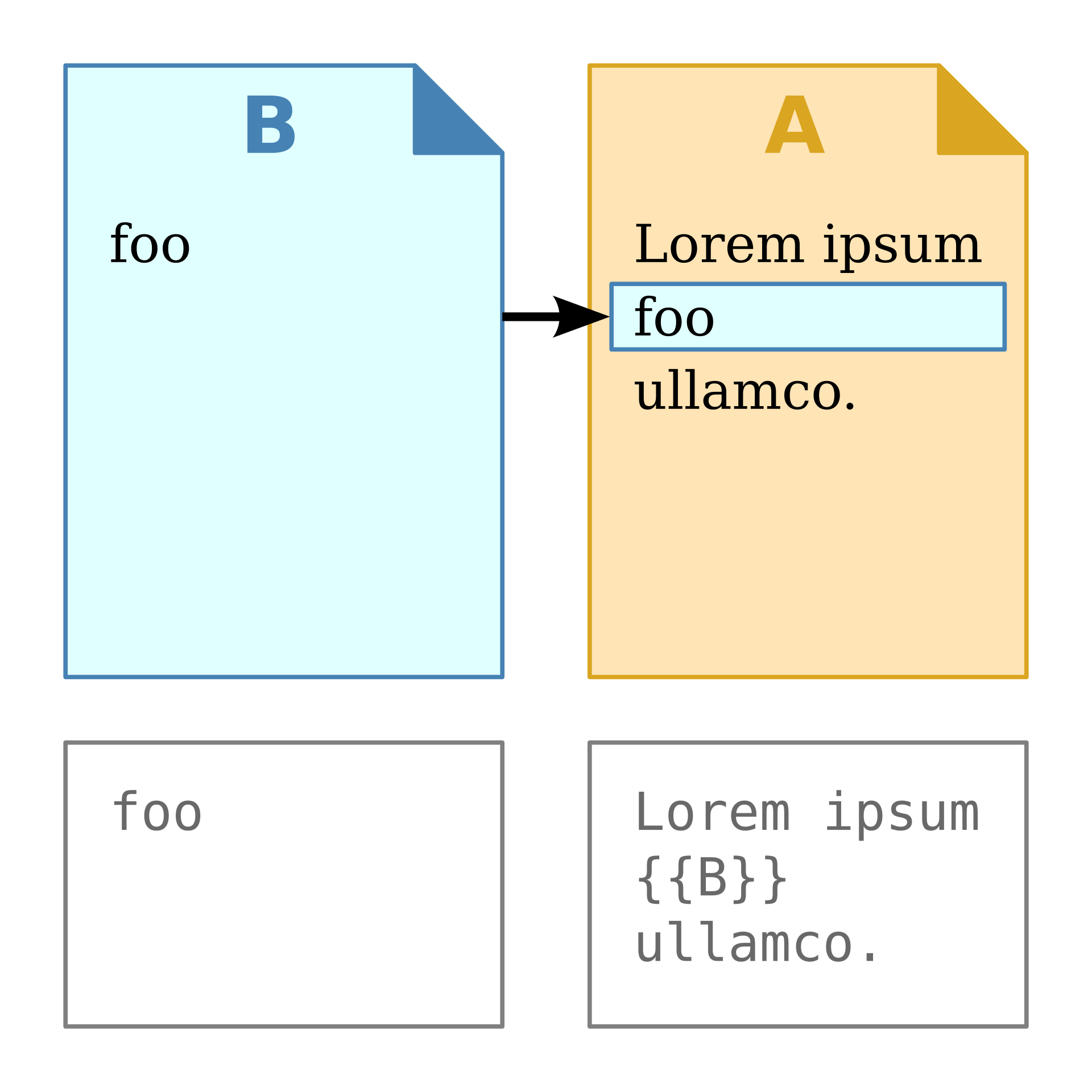

The underlying technology he called “zippered lists” and presented it at a conference of the Association for Computing Machinery in 1965. For quoting and implementing material from other sources he offered “transclusion”, opposite to copy-pasting, where the source gets lost, transclusion embeds a kind of text patch, a part of the original source within a new document and keeps the connection alive. To me one of the most important elements of his vision.

Nelson proposes transclusion, a system combining aspects of inclusion and linking. A transclusive network implements links so as to combine documents dynamically, allowing them to be read together as mutual citations while they remain technically distinct.

As an author himself, Nelson made sure to address some key issues of sharing documents. Firstly he suggested hosting Xanadu decentralised on local machines, so it couldn’t be under the control of a government or large company. This would also ensure the collection’s longevity to survive natural disasters, through sharing copies on many machines.

it is one relatively small computer program, set up to run in each storage machine of an ever-growing network.

Secondly, he tried to find a setup to fairly handle copyright and royalties for users and authors equally. He found micropayments to be the best solution to that, for each transclusion the author would be reimbursed with a small amount of money, depending on the size of the reference. With publishing on the platform authors would have to grant access to their texts.

We need a way for people to store information not as individual "files" but as a connected literature. It must be possible to create, access and manipulate this literature of richly formatted and connected information cheaply, reliably and securely from anywhere in the world. Documents must remain accessible indefinitely, safe from any kind of loss, damage, modification, censorship or removal except by the owner. It must be impossible to falsify ownership or track individual readers of any document.

With this big idea in his head, an ever-growing list of possible enhancements, it turned out to be an immense challenge for Nelson to implement them technically from his ‘outsider’ humanist standpoint. As persuasive as he could be in his arguments, he did infect some investors and programmers with his idea and convinced them to throw money and energy into the project. To cut the long-winded story short, it never took off.

It’s easy (or maybe just funny) to imagine Xanadu as some kind of nightmarish version of Borges’ Library of Babel, a Windows 95–esque software iteration with every conceivable variation of every text ever, all linked to each other in a dense criss-crossed web of sources and citations.

In 1995 WIRED magazine published an article “The curse of Xanadu”, detailing the developments of Nelson’s Idea. Gary Wolf, the author, called Xanadu “the longest-running vaporware project in the history of computing - a 30-year saga of rabid prototyping and heart-slashing despair” (Wolf, 1995) and Nelson, to outline it nicely as “too far ahead of his time”.

The kinds of programs he was talking about required enormous memory and processing power. Even today, the technology to implement a worldwide Xanadu network does not exist.

A programmer who had worked on Xanadu was quoted as quite disillusioned.

He suspected that human society might not benefit from a perfect technological memory. Thinking is based on selection and weeding out; remembering everything is strangely similar to forgetting everything. "Maybe most things that people do shouldn’t be remembered," Jellinghaus says. "Maybe forgetting is good."

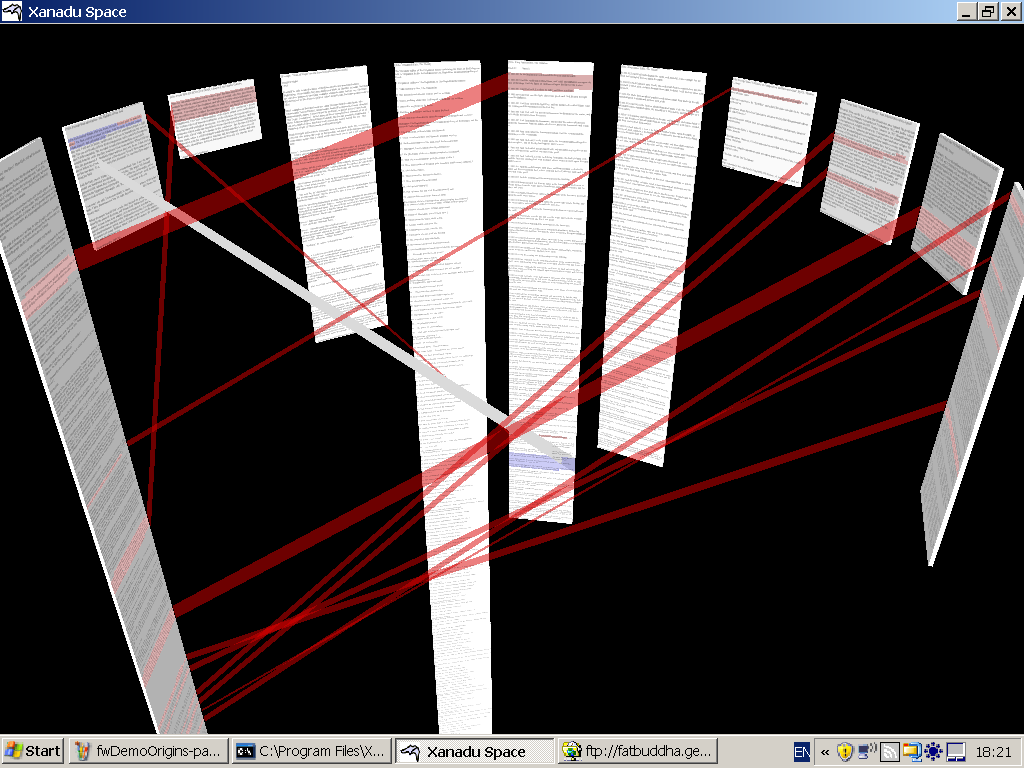

Ted Nelson of course answered the piece with a snappy detailed response. Still, what has been developed and presented to the public under the Xanadu banner to this day are demos and viewers, like Xanadu Space (which - to be fair - features transclusion and a parallel view) but never fully finished products or even a system close to the original vision. To me it seems like Ted had to repeat his credo of the importance of connections so much, he got hung up on the representation of visual links.

What I get from it all, is that the project probably could not withstand the powers of ideology vs. technology and the human factor. Still, his full vision is yet to be matched today and he was able to see the great impact hypertextual content would have in a global shared and networked structure.

A universal hypertext network will make “text and graphics, called on demand from anywhere, an elemental commodity. ... There will be hundreds of thousands of file servers—machines storing and dishing out materials. And there will be hundreds of millions of simultaneous users, able to read from billions of stored documents, with trillions of links among them.” Within a few short decades, this network may even bring “a new Golden Age to the human mind.”

Learn More

- Computer Lib/Dream Machines

- Literary Machines

- Xanadoc working demo

- Demonstration of Xanadu Space

- The Curse of Xanadu | WIRED

- Ted Nelson’s Reaction to the Article

- Podcast about Xanadu by Advent Of Computing

- Ted Nelson in Werner Herzog’s "Lo and Behold"

- Conversation of Ted Nelson and Charles Boroski (Are.na)

- Teds Ted Talk, 1990

“Every talk I give is a Tedtalk. However, that’s been trademarked, so I can’t use it officially.”