The Rise of the Web

To start off with, the World Wide Web (short ‘Web’) isn’t the Internet. Although both terms are often used interchangeably, it is important to understand that those are two different technologies that together form most of the online experiences we have today.

Making geographically distant computers talk to each other was a big challenge. It was possible to send data via telephone lines around the 1960s. Then in the United States, the ARPANET was established and around 1977 the Internet was developed out of it. (Web History Primer, n.d.)

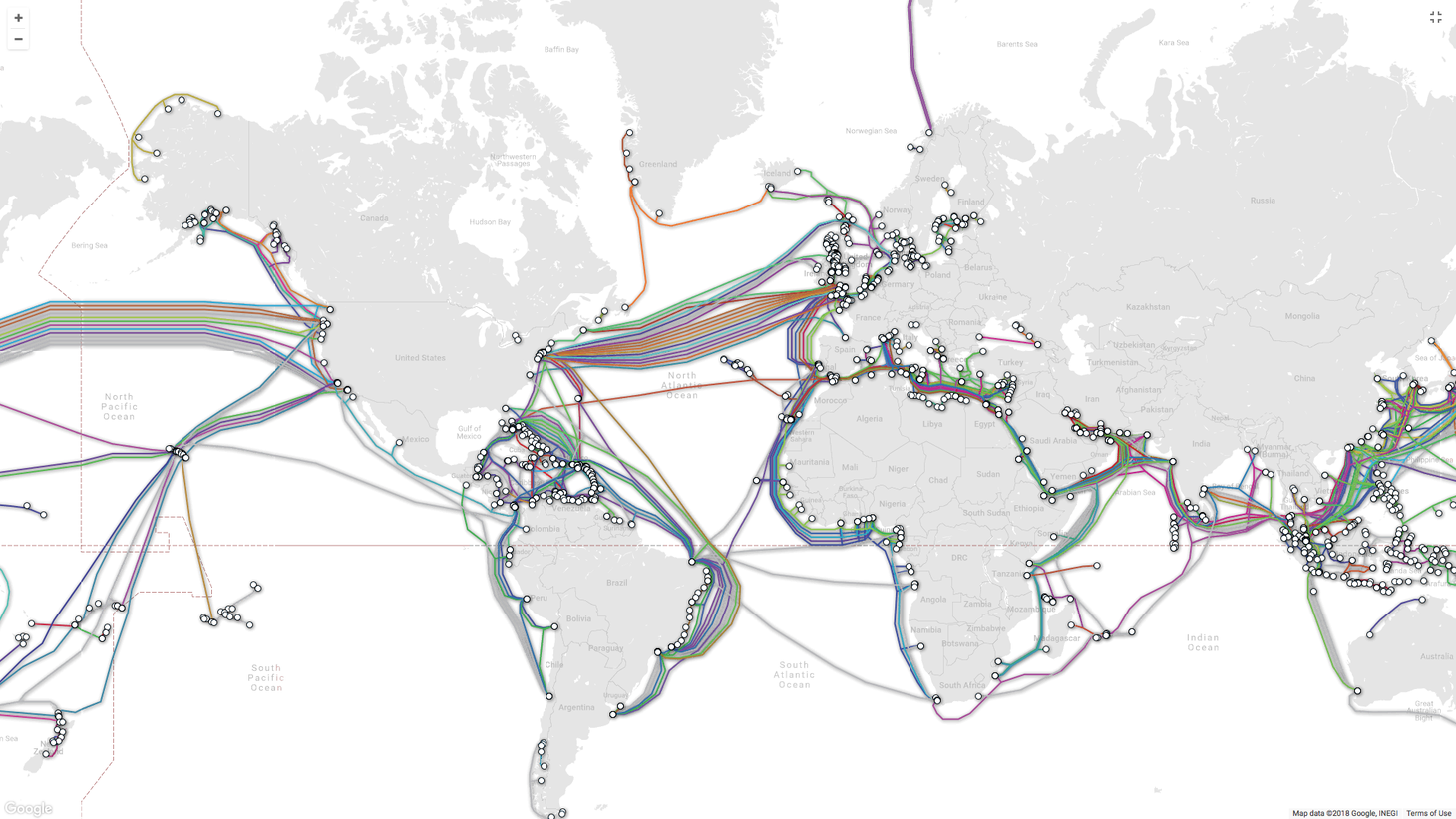

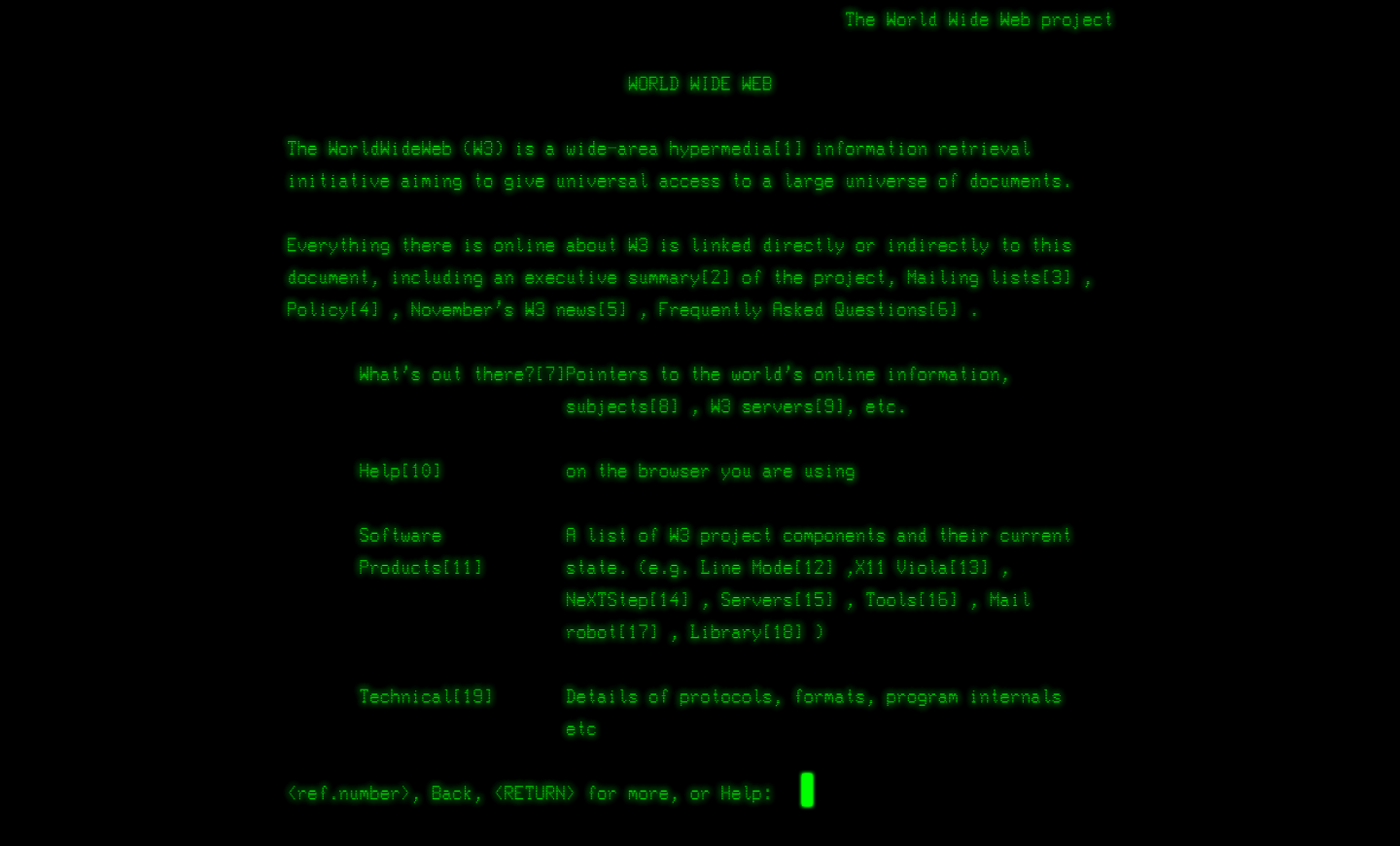

The Internet is the actual network we use to send data from device to device through optical cables. Email for example is one service that’s available via the Internet and predates the Web. The World Wide Web is a hypertext system hosted on the Internet, a distributed collection of documents connected through hyperlinks and accessed with a GUI, the browser.

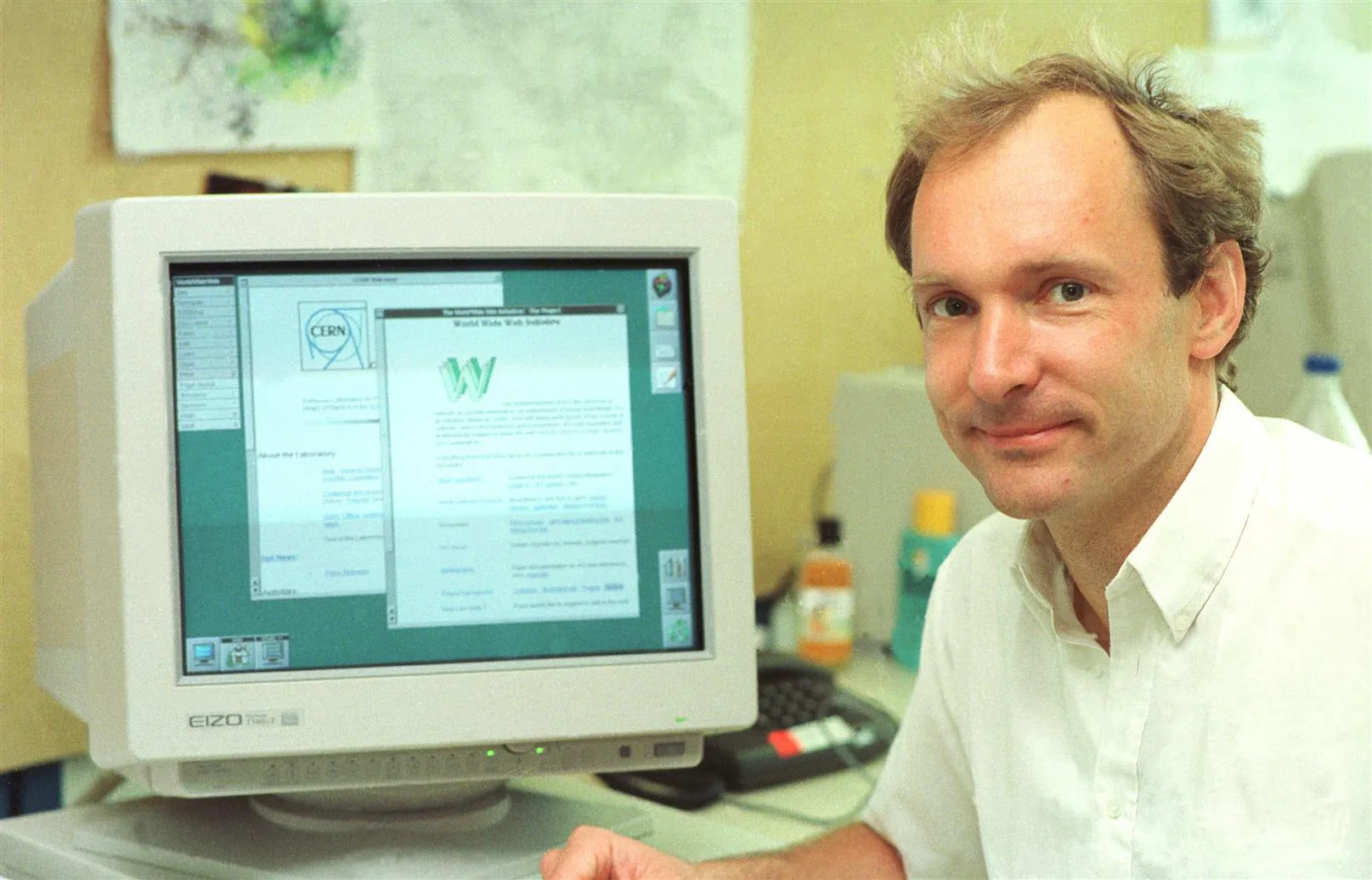

When Tim Berners-Lee joined Cern in 1980 he wrote a hypertext system called “ENQUIRE” as memory support for himself, making connections was an integral part of it. In its aim, it was quite comparable to the hypertext systems introduced in the previous chapter.

Tim's ENQUIRE effectively allowed users to add nodes to a hypertext system. An interesting property was that you could not add a node unless it was linked to something else.

The project started with the philosophy that much academic information should be freely available to anyone.

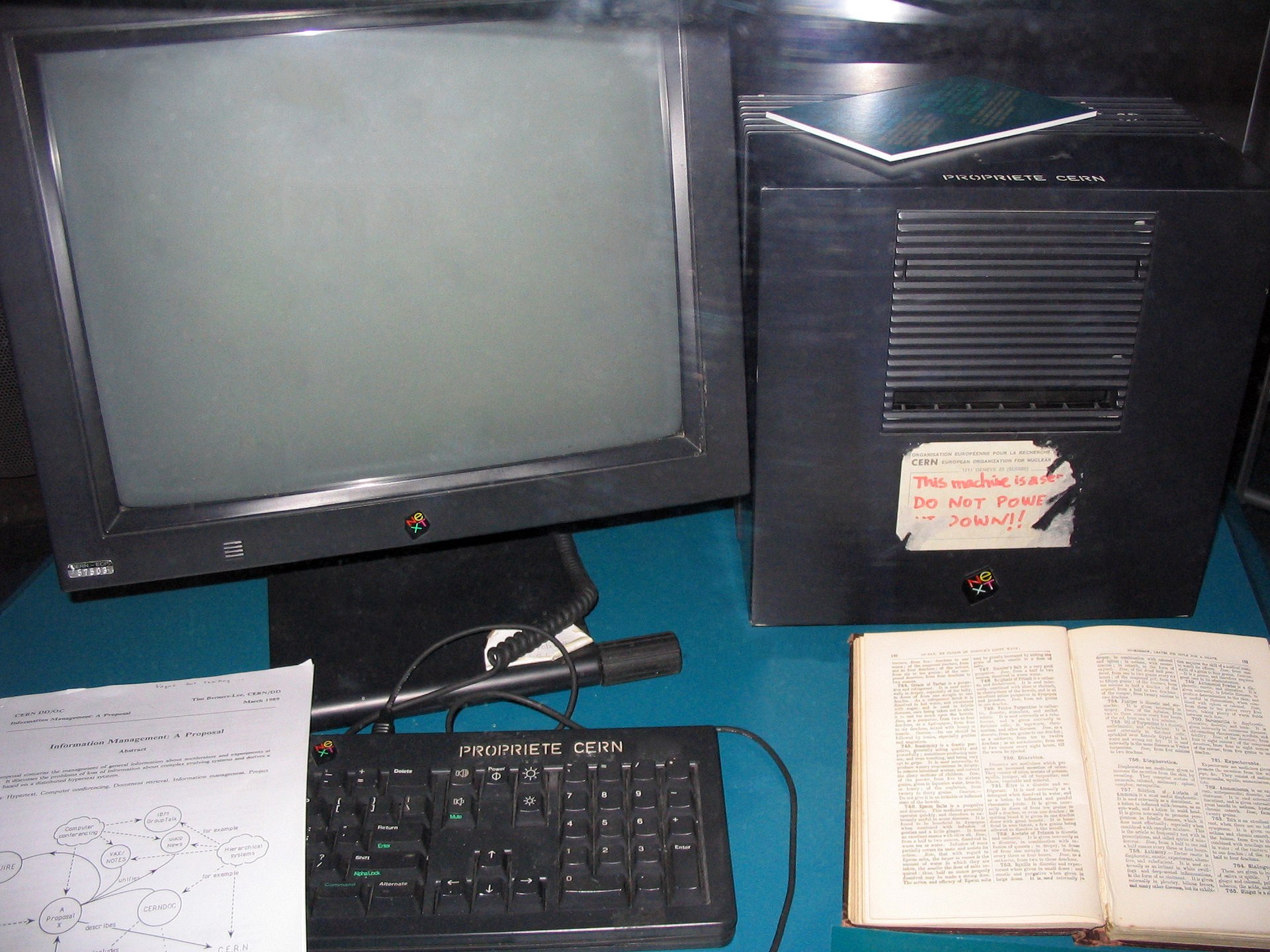

But Tim went a step further than his fellow Hypertext researchers. He wanted to make his system accessible to many people working at CERN, globally, through a real worldwide hypertext system on the Internet. So in 1989, he wrote up a proposal to work on such a project on a NeXT machine, the “WorldWideWeb”. It was granted and by Christmas 1990 he had a working prototype running and the server went live. He had solved the key question, of how to make a browsable hypertext network accessible from very different systems and machines. The Web was born.

The one thing missing was a simple but common addressing scheme that worked between files world-wide.

Tim was joined by Robert Cailliau and Nicola Pellow, who worked on a browser to run on any machine. They established HTML as the shared document markup language, employed the URL to identify documents based on the before-established DNS system and used HTTP as the transfer protocol.

By 1992 the idea took on and there were 50 servers spread over the globe. Marc Andreessen developed the Mosaic browser, which implemented images on websites, rather than opening them in a new window and in early versions pages still could be annotated. Mosaic helped the web take off in the academic sector and by 1993 the web inhabited 2,5% of all Internet traffic (Web History Primer, n.d.). The same year CERN made a crucial decision to put the World Wide Web software under public domain and later released it with an open licence, to “maximise its dissemination” (The Birth of the Web | CERN, n.d.).

In 1994 the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) was founded by Tim Berners-Lee and by 2001 recognized as the controlling body of the web, with its mission to “lead the Web to its full potential”. Its members consist of commercial, educational, and governmental players and individuals (About W3C, n.d.). Ted Nelson commented in ‘Computers for Cynics 6’ that Tim has a very tough political job at the consortium trying to prevent people to put more and more junk into the Web/browser (TheTedNelson, 2012)

1995 was the year commercial players Netscape and Microsoft published the first version of Internet Explorer, with lots of “balls and whistles”, and the first e-commerce marketplaces were established, which grew the Web exponentially. It flourished. This timeframe, the dot-com boom of the 90s, marks the shift from an academic platform for sharing knowledge to a new kind of web, popularised by companies as we know it today.

In the Web’s HTML standard, any element can be a link, but it must be embedded within the document. A text hyperlink is by default displayed in blue and underlined, it can point to other websites or somewhere within the same website. It consists of the ‘href’ attribute, which points to the link’s destination URL and the link text, which will be displayed to the reader. The target attribute can define if it will be opened in a new window or if it will jump within the current browser window.

Learn More

Resonances

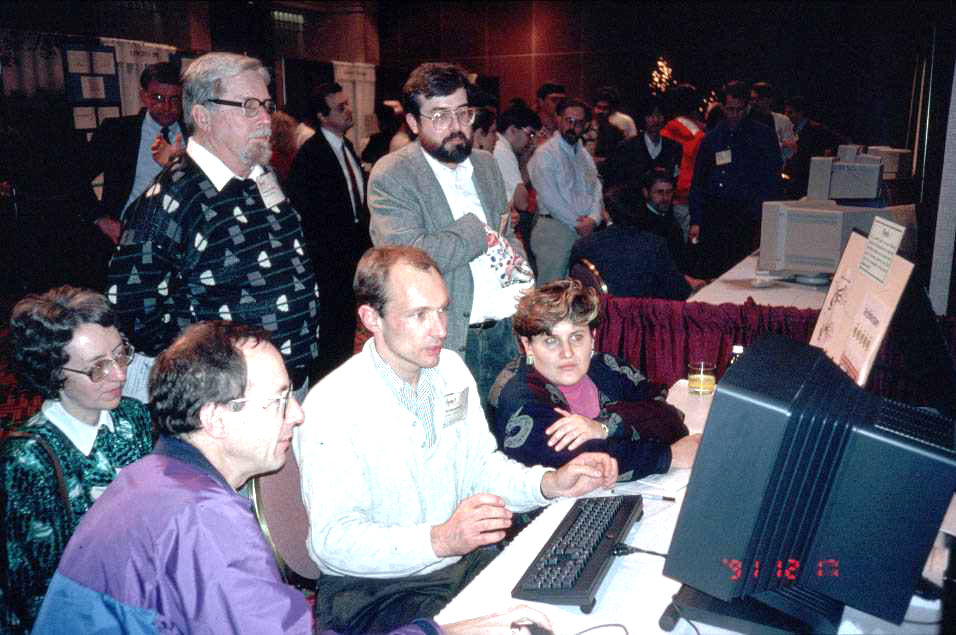

Although his paper had been rejected by the Hypertext ’91 conference, Tim Berners-Lee still brought his ten-thousand-dollar NeXT cube, the only computer running the World Wide Web browser at the time, to present it to the ‘hypertext crowd’ in Texas. (Evans, 2018: 164)

Still, the hypertext community wasn’t impressed. “He said you needed an Internet connection,” remembers Cathy Marshall, “and I thought, ‘Well, that’s expensive.’”

According to Cathy Marshall, a hypertext researcher who spent the majority of her professional career at Xerox PARC working on Note Cards and attended the conference, the Web’s first demonstration to the American public was a disappointment.

Compared with the other systems on display, the Web’s version of hypertext was years behind. Links on the World Wide Web went in only one direction, to a single destination, and they were contextual—tethered to their point of origin—rather than generic, like Wendy’s Microcosm links.

Instead of employing a linkbase that could update documents automatically when links were moved or deleted, the Web embedded links in documents themselves. “That was all considered counter to what we were doing at the time,” Cathy adds. “It was kind of like, well: we know better than to do that.”

Tim’s system didn’t hold up to the functionality standards that the crowd of researchers and hypertext experts at the time expected. Had they only realised that it’s one big advantage, that “very expensive” internet connection, would soon revolutionise the world. After two years there were already 50 websites in place and by 1994 the Web counted 2 million users, with 150,000 new users joining a month (Web History Primer, n.d.).

It certainly didn’t help that the techno-social activities of Hypertext ’91 featured a tequila fountain in the courtyard outside the hotel. The very moment the World Wide Web was making its American debut, everybody was outside drinking margaritas.

Ted Nelson, who already wasn’t happy with some of the developments in pre-web hypertext systems and had dropped out of the FRESS project at Brown as soon as it didn’t realise his full vision of XANADU, indeed wasn’t very happy about the Webs’ success either, as he postulated on his personal Website in pure ASCII text (Wright, 2007: 226).

Nelson, who runs his own YouTube channel, over the years and still repeatedly recites this critique as often as he can, as seen for instance at his self-proclaimed “Angriest and Best Lecture” in 2013.

He is very upset about the ‘bookish’ hierarchical structures that have been dragged along into this new networked medium. It is quite interesting for me, as a Typesetter, to be seen as a representative of that malady.

Markup, XML and the Semantic Web(3.0), which he calls out in ‘I DON’T BUY IN’, are Web technologies that are meant to improve machine readability. For Ted, this direction disregards the qualities of the system he wished for, which would be author-, and with that human-centred.

As Ted points out, the Web turned out to be, to some extent, top-down with “webmasters” being the sole editors of a static website. The previously high-held mantra of user=editor wasn’t fulfilled and with that, his vision of some kind of “re-use of content” e.g. transclusion wasn’t even closely resembled in the Web.

As Alex Wright points out in ‘Glut’, the functionality of links and the normative presence of Web Institutions, like the W3 Consortium are additional issues.

Nelson’s angry dismissal undoubtedly springs in part from personal disappointment at the Web’s ascendance over his own vision for Xanadu, which now seems relegated to the status of a permanent historical footnote. Nonetheless, he correctly identifies many critical limitations of the Web: the evanescence of Web links, the co-opting of hypertext by corporate interests, and the emergence of a new “priesthood” of programmers and gatekeepers behind the scenes who still exert control over the technological levers powering the commercial Web.

In his video series ‘Computers for Cynics’, he sounds much milder and makes clear, he still likes Tim Berners-Lee and credits him for the invention of the URL as his highest achievement, which “Harmonised and standardised network addressing, rational addressing across the diverse structure of Unix, Windows and Macintosh”. Nevertheless, he makes sure to credit all the original inventions that made the web, and with that Tims’ success, possible (TheTedNelson, 2012).

It must have been upsetting to him and others who had worked on, and dreamed about, hypertext systems at the time to see all their work being accredited to one man.

It is important to note that the Web isn’t one big invention, it built up on previous systems and implemented them. With that, it might be a beautiful metaphor for the structure of hypertext itself.

The Web’s popularity has proved a mixed blessing for the original hypertext visionaries. While its success has vindicated their vision, it has also effectively limited the research horizons for many otherwise promising paths of inquiry.